SUNDAY, Feb. 28 (HealthDay News) — Mouse pups whose mothers were exposed to a common but controversial chemical developed allergic asthma, new research has found.

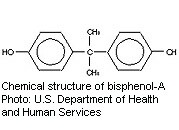

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical commonly found in polycarbonate plastic bottles and the aluminum lining of food and beverage cans. Production of the chemical started about 40 years ago, a timing that scientists note coincides with increasing asthma rates.

Various U.S. health agencies recently pledged $30 million toward short- and long-term research aimed at clarifying the health effects of BPA. It has caused problems in lab animals and in people who have had occupational exposure. On Thursday, Maryland became the third state to tackle the issue, when the state legislature passed a ban on BPA in cups and bottles used by children younger than age 4. Minnesota and Connecticut passed similar laws last year.

Although the newest study looked only at mice, several experts believed that the findings could be worrisome for humans.

“They’re using what are probably going to be reasonable estimates of human neonatal exposure, and that seems to have an effect on the developing immune system or sensitivity to asthma,” said Dr. Steve Georas, chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine and director of the Mary Parkes Center for Asthma, Allergy and Pulmonary Care at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. “If you take it together with some epidemiologic studies, I would consider it cause for concern.”

Dr. Erick Forno, an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine added that “the mice they used are very well-accepted models for asthma and allergies so it should be a very good model of what we would expect to happen in humans, although that is not always the case.”

The findings were to be presented Sunday in New Orleans at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology annual meeting.

Previous studies by the same group had also suggested that pups born to mothers who had been exposed to BPA had an increased susceptibility to allergic asthma. The new study focused on which doses might tip the scale.

The researchers put 0.1, 1 or 10 micrograms per milliliter of BPA in the drinking water of female mice before, during and after pregnancy. Once born, their pups were injected with ovalbumin to make them susceptible to asthma.

Mice born to mothers who had been exposed to 10 micrograms of BPA developed airway problems, though that did not occur among mice born to mothers with lower or no exposure.

“It’s an exciting finding, an initial finding,” Forno said. “I think the next thing is going to have to be not only the level of exposure but also how much or how prolonged does the exposure have to be and if there are any other factors involved.”

The study’s senior author, Dr. Terumi Midoro-Horiuti, an associate professor of pediatrics and biochemistry and molecular biology in the Child Health Research Center at Children’s Hospital, University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, said her group is now collecting cord blood in humans, grouping that according to BPA exposure and following offspring to see if they develop asthma.

A second study being presented at the meeting found that children whose mothers had high levels of folate, a B vitamin, during pregnancy were more likely to develop asthma by the age of 3.

Too little folate, or folic acid, can contribute to neural tube defects in babies.

“This goes along the lines of thinking if some is good, more is better, and we have seen certainly with vitamin supplements, especially with antioxidants, that more is not necessarily better and may be worse,” Horovitz said. “Here we’re seeing it again.”

Data came from 507 mothers of children with asthma and 1,455 mothers of children without asthma, all part of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study.

“In both cases, these studies illustrate how much prenatal environmental influence there is,” Horovitz said.

More information

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology has more on childhood asthma.