WEDNESDAY, March 31 (HealthDay News) — A new study to determine whether a drug prescribed to fight the problems of an enlarged prostate gland can also reduce the risk of prostate cancer promises to prolong a debate that started with an earlier study of a similar drug.

The renewed debate plays out in the April 1 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, which carries not only a report saying that the drug dutasteride (Avodart) may reduce the risk for prostate cancer but also an editorial that counters the upbeat conclusions of the study point by point.

The results of the four-year study of the effect of Avodart on prostate — financed by Glaxo, which markets the drug — seem to mirror those of a 19,000-participant study in 2003 of finasteride (Propecia), which found a 25 percent lower incidence of prostate cancer among men who took that drug than among those who took a placebo.

But that study has been controversial ever since, partly because initial analyses — later discredited — found a higher percentage of aggressive cancers in men taking finasteride.

The new study is different, said Dr. Gerald L. Andriole Jr., chief of urologic surgery at Washington University in St. Louis and lead author of the latest report. Though the two drugs act in the same way, by inhibiting enzymes that cause enlargement of the prostate, Avodart inhibits two such enzymes and Propecia only one, Andriole explained.

“And this trial evaluated men at high risk of prostate cancer,” he said. “Cancers in this group of men are likely to be more significant.”

Risk was evaluated by blood levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which is associated with prostate cancer, and by family history. The study found a 31 percent reduction in prostate cancers in men with a family history of the condition.

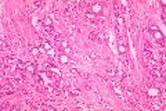

Periodic biopsies, or tissue samples, were used to detect cancers. Most of the cancers that were detected were not the aggressive form that causes major disorganization of the prostate gland. Less aggressive cancers often can be left untreated because they grow so slowly as to be no threat to life.

Andriole said that Avodart is beneficial because it reduces the number of such cancers detected by biopsy. “If we can eliminate diagnosis of these trivial cancers, we can save a lot of worry,” he said. “These cancers tend to be treated because there is a lot of anxiety about them. If we can eliminate some of them, there is a huge benefit in public health terms.”

Because of this, Andriole said, he would consider prescribing Avodart for cancer prevention to a man at high risk because of high PSA levels or family history, though the drug is not approved for that purpose by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

That’s not good, said Dr. Patrick C. Walsh, a professor of urology at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, who wrote the accompanying editorial.

“When you look at the results, they are very similar to those of the finasteride study,” Walsh said. “Dutasteride reduces by 23 percent the incidence of non-lethal cancers that men never knew they had.”

The cancers detected in the study were found by biopsies that would ordinarily not be done because there were no indications of risk. Biopsies done in the study on men known to be at higher risk because of PSA levels found no difference in cancer incidence between those taking the drug and those taking the placebo, Walsh said.

And there is potential danger for men who take the drug, he said, because Avodart lowers the blood levels of PSA so that a warning increase might go unnoticed. “If their PSA level goes up, the chance of having a potentially lethal form of cancer is sixfold higher,” he said.

Men who look for guidance on the issue shouldn’t expect help from specialist societies. Guidelines issued last year by the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Urological Association carefully sidestep the issue, saying that men should discuss it with their physicians.

Even those guidelines have become part of the debate.

Andriole said the new study may cause newer guidelines to be “a bit less ambiguous about wording,” whereas Walsh noted that the guidelines said that the potential for an increased incidence of aggressive cancers had to be weighted against the possible benefit of the drug.

More information

The U.S. National Cancer Institute has more on prostate cancer.