MONDAY, May 3 (HealthDay News) — Using magnets to stimulate the brain may ease depression in people who have not found relief from antidepressants, new research has found.

“We have settled a fundamental question about [transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS] therapy, which is: ‘Does it work?'” said the study’s lead author, Dr. Mark George, a professor of psychiatry, radiology and neuroscience at the Medical University of South Carolina. “The answer is ‘yes.'”

The researchers administered the magnet therapy to half of a group of 190 adults who had been depressed for at least three months, but not longer than five years, and who had taken medication for depression but were not helped. The others were given a sham treatment — simulated magnet therapy that was mostly indistinguishable from the real thing, the researchers said.

After three weeks, about 14 percent of those receiving magnet therapy were no longer depressed, compared with 5 percent who were getting the fake treatment.

The researchers continued the magnet treatment for three more weeks for those who were still depressed and also offered the real treatment to participants who’d gotten the sham treatment.

After that period, about 30 percent were no longer depressed, the researchers said.

“In a rigorous, industry-free multisite trial with a convincing sham, we found unambiguously that TMS worked better than the sham. It’s watershed,” George stated.

The findings are published in the May issue of Archives of General Psychiatry.

Psychiatrists have been interested in the possibilities of treating depression with magnet therapy for more than a decade, the experts said. Magnets are believed to work by creating electrical currents in the nerve cells in the left prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain involved with regulating mood. The current may jump-start the area, which has been shown to be underactive in people who are depressed, George said.

But testing magnet therapy has been difficult. “Double-blind” studies, in which neither the researchers nor participants know who is getting the real treatment and who is getting the fake, have been difficult to carry out.

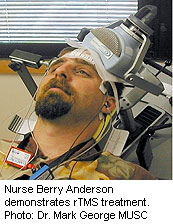

The current study overcame that by creating an elaborate sham. During magnet therapy, participants were painlessly zapped by a pulsing electromagnetic coil 3,000 times over 37 minutes. The current created a head-tapping sensation that some people said reminded them of a woodpecker, George said.

The coil, which is aimed at the brain area to be stimulated, creates a magnetic field that passes through the skin and skull, inducing an electrical current in the brain.

Participants receiving the sham treatment felt the same head-tapping, but a metal insert below the magnet blocked the magnetic field from entering the brain while electrodes on the scalp delivered the tapping sensation.

Using electrical current to treat brain disorders has been around in some form since the 1940s and 1950s, said Tony Tang, an adjunct professor in the psychology department at Northwestern University. However, electroconvulsive, or electroshock, therapy can induce seizures, and some studies showed it might cause memory loss and brain damage. Though effective in some people, electric shock was viewed with suspicion by the public, and today is used only as a last resort, Tang said.

Magnet therapy is essentially a much gentler, less invasive form of electric shock therapy, Tang said.

“Transcranial magnet therapy is one of the most exciting new developments in our field,” Tang said. “There are new drugs coming out every year, but they are all fairly similar to each other, and we don’t see much difference in efficacy. With TMS, the mechanism is completely different. It’s a very, very safe and gentle, noninvasive way to do electric shock therapy.”

In 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the marketing of a device used for magnet therapy to treat depression that is considered mildly resistant to treatment, according to background information on the study provided by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, which funded the study.

The next step, the researchers said, is to fine-tune the treatment to determine if higher levels of magnetic stimulation or changing the location of the magnetic coil might be even more effective or if magnet therapy might work best in conjunction with medications.

In the study, the only significant side effects were headaches and mild discomfort at the stimulation site. Most participants remained depression-free for several months after treatment stopped, according to the study.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health has more on depression.