SUNDAY, June 2 (HealthDay News) — A drug already used for advanced kidney and liver cancers may help slow the progression of thyroid cancers that do not respond to standard treatment, a new clinical trial finds.

Researchers found that the drug, called sorafenib (Nexavar), taken as a pill, nearly doubled the length of time that patients remained progression-free — from about six months to 11 months.

It’s not a cure, and no one knows yet whether sorafenib can ultimately extend people’s lives. But experts said the findings offer some hope to a group of patients who currently lack good options.

“If we can control the disease, and do it with tolerable toxicity, that’s a good thing,” said Dr. Gregory Masters, a medical oncologist who was not involved in the research.

In general, thyroid cancer is a highly curable disease. But about 10 percent of patients do not respond to the mainstays of treatment: surgery and radioactive iodine, a form of radiation taken by liquid or pill.

On average, those patients survive for another two to three years, said Dr. Marcia Brose of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, the lead researcher on the new study.

“We’ve taken a big step with this study,” Brose said. “The message for these patients is that there is hope.”

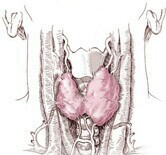

The findings come from an international trial of 417 patients with thyroid cancer that had failed to respond to standard treatment and had spread beyond the thyroid — a gland in the neck that secretes metabolism-controlling hormones.

About half of the patients were randomly assigned to take sorafenib, while the rest were given inactive placebo pills. Overall, 42 percent of sorafenib patients had no cancer progression for at least six months, versus one-third of placebo patients. And 12 percent of patients on the drug saw their tumors shrink by 30 percent or more — versus 0.5 percent of the placebo group.

Brose is scheduled to present the findings Sunday at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, in Chicago. She is a paid consultant to Bayer HealthCare and Onyx Pharmaceuticals, which co-market Nexavar and funded the trial.

Because this study was presented at a medical meeting, the data and conclusions should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Sorafenib has not yet won approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat thyroid cancer. If it does, it would be the first new drug for the disease in almost 40 years.

The thyroid is a gland in the neck that secretes hormones involved in metabolism. Thyroid cancer, which is diagnosed in about 60,000 Americans each year, has a high cure rate — a fact that, in a way, has worked against the few patients with resistant tumors, Brose said.

“It’s given the misperception that this disease is all wrapped up,” she said.

Still, it’s not that there has been no research into ways to help patients with resistant thyroid cancer, Brose pointed out. But the chemotherapy drugs that have been tried have met with little success. Doxorubicin was the last drug approved for advanced thyroid cancer, back in 1974, but doctors rarely use it because its benefits are minor and its side effects are severe.

But now there are newer, so-called targeted chemotherapy drugs that are designed to zero in on tumor cells and spare more healthy cells. Sorafenib is one of those; it’s in a class called kinase inhibitors, and it blocks certain enzymes that help feed the growth and spread of tumor cells.

“We’re excited to have an option for these patients that has less toxicity,” said Masters, a spokesperson for ASCO who specializes in cancers of the throat and chest. And because it’s an oral medication, he added, it spares people from having to come to the hospital for treatment.

In the trial, the most common side effects were skin reactions on the hands and feet, diarrhea, hair loss, fatigue and weight loss — which is what’s been seen with the drug in other cancers. “The side effects were tolerable to patients,” Brose said.

There are still unanswered questions — including whether sorafenib gives patients a shot at a longer life. “We won’t know that for a few years,” Brose said. And there’s no way to predict whether or when the FDA will clear the drug for thyroid cancer.

Because sorafenib is approved for other cancers, doctors can use it on an “off-label” basis for thyroid cancer. However, that makes insurance coverage a thornier issue, and the drug costs several thousand dollars a month.

“Most people would not be able to pay for it on their own,” Masters said. Insurance companies may pay, he noted, but doctors need to work it out with health plans on a case-by-case basis.

If the FDA approves sorafenib specifically for thyroid cancer, that would make insurance coverage much easier for patients, Masters said.

He added that sorafenib is not the only drug under study for resistant cases of thyroid cancer; other types of newer, targeted medications are being tested.

Study author Brose said that should be welcome news to a group of patients who may have thought their disease was forgotten. “There are options out there,” she said, “and researchers are pursuing them.”

More information

Learn more about thyroid cancer from the American Cancer Society.