TUESDAY, Feb. 16 (HealthDay News) — King Tut probably wasn’t killed by a vengeful wife and power-hungry advisors but by a combination of malaria, a broken leg and several inherited disorders that rendered him weak and lame long before his actual death, new DNA and radiological evidence suggests.

“What these scholars are suggesting — and you can’t prove it definitively — is that he probably broke his leg, but it was in the midst of a malarial crisis and, on top of all his other problems, led to his demise,” said Dr. Howard Markel, author of an editorial that accompanies the revelatory article in the Feb. 17 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The genetic tests also enabled Egyptologists to identify and give names to various members of the royal family from that time, including King Tut’s parents, grandparents, great grandparents and siblings.

“They’ve answered some very interesting questions,” said Dr. Randall C. Thompson, a professor of medicine at the University of Missouri, and an attending cardiologist with the Mid-America Heart Institute, both in Kansas City.

Thompson was co-author of a study, published last year in the same journal, that used CT scans to show that mummies up to 3,500 years old had hardening of the arteries, a disease once thought to be a scourge of modern society.

Asked if he thought this would be the final nail in the coffin of sensationalist theories attributing Tut’s death to a bludgeoning by his wife, who was also his sister, Dr. David Mininberg, a New York City physician who also holds a degree in Middle Eastern Art and is an expert in the medicine of ancient Egypt, said, “God, everybody hopes so. That murder-conspiracy theory was based on a lot of inaccurate or sloppy reading of the available material and a lot of conjecture.”

The current study, by contrast, he said, is “terrific, really first-rate . . . They’re not claiming more than they can substantiate.”

Other theories about King Tut’s death that have circulated over the years include being kicked in the head by a horse, septicemia and poisoning. One study appearing four years ago attributed the pharaoh’s death to a festering leg wound.

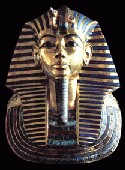

Although Tutankhamun reigned for only nine years, until 1324 B.C., he has remained the most fascinating and famous of all the pharaohs. His tomb was discovered in 1922.

From September 2007 to October 2009, a team of experts, led by Zahi Hawass of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo, conducted a series of radiological, genetic and other tests on 11 royal mummies from Tut’s period.

The results of this belated autopsy: King Tut had probably been weakened by a spectrum genetic of disorders, including possibly Kohler disease, a disorder of the foot, which may also have been related to his club foot, flat arches and malformed toes.

This explanation is given credence by the fact that 130 whole or parts of sticks that could have been walking canes were found in Tut’s tomb.

Several other members of the royal family also had malformations while four had malaria, although it’s unclear if this is what actually killed them.

“We assumed that malaria was present back in those days but didn’t know for sure. This is the earliest dating,” Thompson said.

In the course of the DNA testing, several mummies without names assumed clear identities.

The mummy formerly known as KV35EL was identified as Tiye, Tut’s grandmother, and KV55 as Akhenaten, Tut’s father.

“It’s a very intriguing family tree,” said Markel, who is director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor. “They demonstrated a level of intermarriage between siblings.”

The study also laid to rest rumors that members of the royal family suffered from Marfan syndrome or a hormonal imbalance that led them to appear feminine.

“Some statues of Tut’s father show him grotesquely deformed, and historians wondered if he’d had some kind of feminizing disorder or was it just the artistic style,” Thompson said. “These researchers answered the question.”

As genetic and other tests continue to be developed and honed, Markel brought up ethical considerations about digging up remains.

“Most of us don’t want our graves to be disrupted; those are the kinds of things we want to think about very carefully,” he said. “The Egyptologists doing this study actually thought very deeply about it and had a bioethicist consulted.”

And while, at least for now, this seems like it could be the final autopsy on the long-dead king, “technology is a shifting target and there might be things that become available in the future that might be yet another way to analyze this,” Mininberg said.

More information

Learn more about mummies at the Smithsonian Institution.