MONDAY, Nov. 23 (HealthDay News) — Problems with the popular arthritis drug Vioxx, including increased risk for heart attack, stroke and death, were known for years before the drug’s voluntary withdrawal from the market in 2004, a new report says.

Contrary to claims by the manufacturer, Merck & Co., dangerous side effects were evident in 2000, a year after the drug was put on sale, but independent investigators lacked access to all the clinical trial data, so no one voiced concerns until four years later, say the authors of the latest look at the controversy.

In a statement released Tuesday, Merck officials said this: “Merck believes the article published in The Archives of Internal Medicine in today’s issue related to Vioxx used unreliable methods and reached incorrect conclusions.”

“The first time Merck observed a difference in a placebo-controlled study was when it

learned the results of the APPROVe study in September 2004. We voluntarily withdrew Vioxx from the market within a week of those results,” the statement continued.

“Merck acted responsibly — from researching Vioxx prior to approval in studies with

approximately 10,000 patients to monitoring the medicine while it was on the market — to voluntarily withdrawing the medicine when it did,” the statement said. “Our decisions were based on the data from well-controlled clinical trials.”

But the authors of the new study believe the Vioxx saga points to a larger problem, one that involves the drug approval process in the United States.

“One of the challenges in health care is to recognize these safety risks early,” said lead researcher Dr. Joseph S. Ross, an assistant professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

The trials that drug companies conduct to get U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval are too short and are usually not designed to uncover safety problems, Ross said.

“There is no mandate to publish the trials, so if you don’t have access to the FDA records, you don’t know what the drug risk is,” he said. “Once it’s approved, maybe or maybe not, the trial continues to be studied, and even then, there is no mandate to publish the findings.”

The report, published in the Nov. 23 issue of the Archives of Internal Medicine, should be used to better understand drug safety, Ross said.

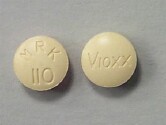

Ross’s group set out to test the truth of a statement by Merck’s chief executive officer before a U.S. Senate committee in November 2004 that earlier clinical trials showed no difference in the risk of heart events between patients taking Vioxx (rofecoxib) and those taking a placebo.

The researchers found 30 trials with a total of 20,152 patients, comparing the anti-inflammatory medication with placebo.

Twenty-one of those trials had been completed by the end of December 2000, and a risk of heart attack, stroke and death among patients taking Vioxx was clear and should have led to a safety warning, Ross said.

The risk for those cardiovascular events was 35 percent higher among patients taking Vioxx compared with those taking placebo. The association grew as more trials were completed, increasing to 39 percent in April 2002, when newer data was analyzed, and to 43 percent in September 2004, according to the study.

“Physicians and the public deserve to be in a position to make informed choices about risks and benefits, and the disclosure and dissemination of information about potential risk immediately after its recognition is absolutely essential. Our study provides insight into what should have been known about the risks of rofecoxib,” the authors wrote. “If we are to detect harms early and protect the public’s health, while ensuring the availability of new, clinically effective therapeutics, a system must be established that makes full use of all existing evidence.”

A similar drug, Bextra, was also pulled from the market for safety concerns, but Celebrex, a drug in the same class as Vioxx, remains available.

Dr. Steven E. Nissen, chairman of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic and one of the early watchdogs of Vioxx, hailed the findings. “This remarkable manuscript provides compelling evidence that the adverse cardiovascular effects of rofecoxib could have been detected several years prior to the withdrawal of the drug.”

The findings highlight the need for major changes in the current system for development, approval, promotion and post-marketing surveillance of drugs in the United States, he added.

“We need full transparency in the reporting of adverse events observed during development and early usage of all drugs, but particularly for new molecular entities such as rofecoxib,” Nissen said. “Selective publication of favorable findings have repeatedly concealed serious safety risks.”

“Aggressive marketing, through industry-sponsored Continuing Medical Education and direct-to-consumer advertising, have facilitated overuse of new agents before their full benefits and risks could be assessed,” he added. “Finally, a weak system for post-marketing surveillance has allowed unsafe medications to remain on the market long after evidence of an unfavorable risk-benefit relationship might have been detected.

Since the Vioxx episode, the FDA has tightened some requirements. As of 2007, results of clinical trials must be posted on an FDA Web site within a year of a trial’s conclusion.

Still more is needed, experts like Nissen believe. “It is an unfortunate legacy of the Vioxx debacle that the problems that led to this public health catastrophe remain unresolved,” Nissen said. “Sadly, this could happen again.”

More information

For more information on how drugs are approved, visit the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.