FRIDAY, Jan. 4 (HealthDay News) — Though it began as a treatment for something else entirely, gastric bypass surgery — which involves shrinking the stomach as a way to lose weight — has proven to be the latest and possibly most effective treatment for some people with type 2 diabetes.

Just days after the surgery, even before they start to lose weight, people with type 2 diabetes see sudden improvement in their blood sugar levels. Many are able to quickly come off their diabetes medications.

“This is not a silver bullet,” said Dr. Vadim Sherman, medical director of bariatric and metabolic surgery at the Methodist Hospital in Houston. “The silver bullet is lifestyle changes, but gastric bypass is a tool that can help you get there.”

The surgery has risks, it isn’t an appropriate treatment for everyone with type 2 diabetes and achieving the desired result still entails lifestyle changes.

“The surgery is an effective option for obese people with type 2 diabetes, but it’s a very big step,” said Dr. Michael Williams, an endocrinologist affiliated with the Swedish Medical Center in Seattle. “It allows them to lose a huge amount of weight and mimics what happens when people make lifestyle changes. But, the improvement in glucose control is far more than we’d expect just from the weight loss.”

Almost 26 million Americans have type 2 diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association. Being overweight is a significant risk factor for type 2 diabetes, but not everyone who has the disease is overweight. Type 2 occurs when the body stops using the hormone insulin effectively. Insulin helps glucose enter the body’s cells to provide energy.

Lifestyle changes, such as losing 5 to 10 percent of body weight and exercising regularly, are often the first treatments suggested. Many people find it difficult to make permanent lifestyle changes on their own, however. Oral medications are also available, but these often fail to control type 2 diabetes adequately. Injected insulin can also be given as a treatment.

Surgeons first noted that gastric bypass surgeries had an effect on blood sugar control more than 50 years ago, according to a review article in a recent issue of The Lancet. At that time, though, weight-loss surgeries were significantly riskier for the patient. But as techniques in bariatric surgery improved and the surgical complication rates came down, experts began to re-examine the effect the surgery was having on type 2 diabetes.

In 2003, a study in the Annals of Surgery reported that 83 percent of people with type 2 diabetes who underwent the weight-loss surgery known as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass saw a resolution of their diabetes after surgery. That means they no longer needed to take oral medications or insulin in most cases.

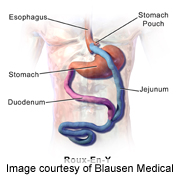

In Roux-en-Y surgery, the anatomy of the digestive system is rearranged, Sherman explained. A small portion of the stomach is attached directly to the small intestine, bypassing the rest of the stomach, duodenum and upper intestine. This not only restricts how much food the person can eat — as do other weight-loss surgeries, such as gastric banding — but it changes the hormones in the digestive system.

“When food or nutrients enter the mid or hind intestine, the body releases a hormone called GLP1 and other hormones that tell the brain to stop eating,” Sherman said. After gastric bypass surgery, however, “you’re getting this effect earlier in a meal, and it results in less cravings, too,” he said. “It’s unclear exactly where the mechanism for this change is right now, though some suspect the duodenum.”

Wherever the change occurs, it happens soon after the surgery. “There’s a change in blood glucose almost immediately, often before people even leave the hospital,” he said.

Sherman noted that weight-loss surgery that involves banding doesn’t have the same effect on diabetes. Once people lose weight, their blood sugar control may improve, he said, but it’s not as dramatic as what occurs after bypass surgery.

Potential risks of gastric bypass include those that exist for most surgeries, including the possibility of excessive bleeding, blood clots and infection, according to the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. But, these risks are often heightened in people who are obese.

Afterwards, people who’ve had the surgery may not absorb nutrients as well as they used to, and doctors often recommend taking certain supplements. Also, food can tend to move from the stomach to the small intestine too quickly, before it’s fully digested. Called dumping syndrome, this side effect often develops after eating foods high in carbohydrates, according to Sherman. Symptoms may include abdominal pain and diarrhea.

And, despite its promise, not everyone with diabetes is an ideal candidate for gastric bypass.

It’s currently recommended only for those with a body mass index (BMI) above 40 and those who have a BMI over 35 and a medical condition such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure or heart disease.

Type 1 diabetes, though, is not on the list. Williams noted that bariatric surgery won’t help with blood sugar control in people with type 1 diabetes because type 1 is an autoimmune condition in which insulin-producing cells in the pancreas are destroyed by the immune system. In type 2, Sherman said, the problem is not in the pancreas to begin with.

Gastric bypass surgery is also best for those who haven’t had type 2 diabetes for a long time, and for those who don’t have to use insulin to control their blood sugar.

“Bariatric surgery is not an easy fix,” Williams said. “There’s a lot of prep that goes into bariatric surgery, and then it’s a lifelong lifestyle adjustment. Dietary intake is restricted for life, and people have to avoid high-sugar foods. But, it’s a really good option for the right person.”

More information

The U.S. National Library of Medicine has more about gastric bypass surgery.

Learn about one man’s experience after weight-loss surgery, here.