WEDNESDAY, Nov. 3 (HealthDay News) — When Medicare cut its reimbursement rates for hormonal treatment for men with prostate cancer, use declined drastically.

But patients who really stood to benefit from the treatment — androgen-deprivation therapy — still received it, researchers report in the Nov. 4 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Probably what we’re witnessing here is how physicians potentially respond to financial incentives and issues of medical uncertainty,” said study author Dr. Vahakn Bedig Shahinian, an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor. “That probably cuts across a variety of medical scenarios having nothing to do with prostate cancer.”

Other experts agreed.

“Clearly, there are other areas where this would occur, even in other areas of prostate cancer right now. For instance, proton beam radiation therapy reimburses very well so there are certain medical centers that are really pushing it,” agreed Dr. Judd W. Moul, chief of the division of urologic surgery at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

“Another classic example is imaging,” Moul said. “CAT scans reimburse pretty well so a lot of doctors put CAT scan units into their offices. That’s a profit center.”

The Medicare Modernization Act that went into effect in 2004 and 2005 slashed physicians’ reimbursement for androgen-deprivation therapy by about 50 percent.

In the 1990s, when reimbursement rates were much higher, the number of men receiving the therapy exploded. The treatment is considered effective in more advanced, higher-risk cancers and not so useful in those with low-grade tumors still confined to the prostate, although new evidence on hormonal therapy continues to emerge.

“There was a significant difference between what the doctors were able to buy the drugs for and what Medicare would cover when they were administered,” said Moul. “The bottom line is they were very profitable for the physicians.”

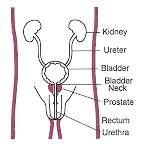

To assess the impact of the Modernization Act, Shahinian and his colleagues looked at records of almost 55,000 men diagnosed with prostate cancer between 2003 and 2005. Patients were separated out based on the characteristics of their tumors — for example, localized vs. locally advanced, and whether evidence existed to support use of this therapy in those cases. An intermediate category was established for cases where the decision was less clear-cut.

Unnecessary use of androgen-deprivation therapy declined from 38.7 percent in 2003 to 30.6 percent in 2004, then to 25.7 percent in 2005, the study authors reported.

But there were no changes in appropriate use of the therapy, which stayed stable, the researchers said. Meanwhile, gray-zone use declined in 2005, but not the prior year.

Research identifying some adverse effects of hormonal therapy may also have contributed to the reduction, the authors said.

Whether these findings — or whether similar reimbursement changes in other areas — will affect the U.S. health-care system isn’t clear, especially with the current push towards personalized medicine.

“It’s very subjective. There are no hard-core guidelines. There are suggestions,” Moul said. “In general, you want to use hormone therapy in higher-risk men who have worse disease but there’s a fairly significant gray zone,” he pointed out.

“There’s probably many, many areas where the system could be tightened up, where we could save money but the downside is going to be a lot of individual patients who are going to be mad because they can’t get what they want to get,” he added.

Shahinian is a consultant for the biotechnology firm Amgen. The American Cancer Society funded this study.

More information

The American Cancer Society has more on androgen deprivation therapy.