TUESDAY, July 27 (HealthDay News) — Taking advantage of recent discoveries of more genetic variants that raise the risk for breast cancer, European scientists have analyzed those variants in relation to breast cancer and found that the risk is greater with certain variants and for certain tumor types.

In the short term, the findings are expected to be of the most use to scientists in their effort to understand the biology of the disease.

“Our findings suggest that, at present, this type of polygenic risk score is unlikely to be a useful tool for population-based screening programs, but may be relevant for understanding biological mechanisms,” said Dr. Gillian Reeves, a staff scientist at the Cancer Epidemiology Unit at the University of Oxford. She led the study, which is published in the July 28 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

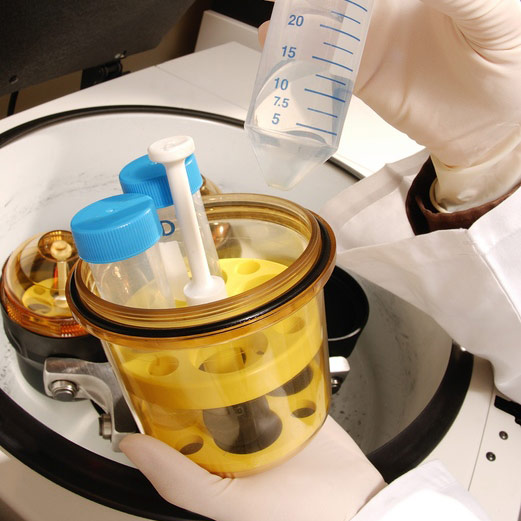

The study looked at more than 10,000 women with breast cancer, who were on average 58 years old when diagnosed, and more than 10,000 without breast cancer. All provided blood samples for genotyping in the years 2005 through 2008.

Reeves and her colleagues looked at 14 different alterations known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), small genetic changes within a person’s DNA sequence that are associated with disease, and then tried to create a polygenic risk score.

They found the risk of breast cancer greatest for two SNPs and greater for estrogen receptor-positive forms of breast cancer than for ER-negative disease. In ER-positive tumors, estrogen fuels the tumor’s growth.

“When the effects of the seven SNPs most strongly related to overall breast cancer risk were combined using a polygenic risk score, the cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 70 among women in the top fifth for such a score was twice that among women in the bottom fifth, 8.8 percent versus 4.4 percent,” Reeves said. But the risk was greater for ER-positive disease than for ER-negative disease, the researchers found.

Reeves did not find that there were any interactions between the effects of the genes she researched and other, established risks for breast cancer.

The new study drew praise from another expert, Dr. Douglas Easton, a professor of genetic epidemiology and director of cancer research at the U.K. Genetic Epidemiology Unit, Strangeways Research Laboratory in Cambridge, U.K. “It’s a nice study which takes the genetic markers which we and others have identified and estimates their effects in a prospective study.”

The findings that some of the SNPs are more strongly associated with ER-positive breast cancer reflect his own findings. Overall, he said, the predictive values of the SNPs is relatively weak.

Since the Reeves study, Easton said, his team has identified seven additional SNPs that appear to be linked to breast cancer risk.

“There are now about 20 known susceptibility SNPs,” he said. “As further SNPs are identified, the predictive value of these markers will clearly improve.”

Soon, he said, SNPs for predicting ER-negative disease more strongly may also be discovered.

More information

To learn more about estrogen receptor-negative cancers, visit the U.S. National Cancer Institute.