MONDAY, July 26 (HealthDay News) — Extending the time window to treat stroke patients with the clot-dissolving drug tPA from 3 hours to up to 4.5 hours after the onset of stroke doesn’t result in any significant delays in treatment and appears to be a safe option for saving lives, new research suggests.

Still, there was a slight increased risk of death and bleeding over a three-month period in patients who received the later treatment — a finding that reinforces the idea that the treatment should be given as soon as possible after a stroke to ensure better outcomes, said Swedish researchers reporting in the July 26 online edition of The Lancet Neurology.

“We’re still targeting to treat as early as you can because that gets the best results,” said Dr. Roger Bonomo, director of stroke care at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “But this gets people included in the treatment group who otherwise would have been excluded just because it was 3 hours and 1 minute or 3 hours and 10 minutes after the stroke,” he explained.

“The study is saying that the safety is sufficient to warrant continuing to treat patients [with tPA up to 4.5 hours after a stroke] even though these people have more symptomatic hemorrhages,” he added.

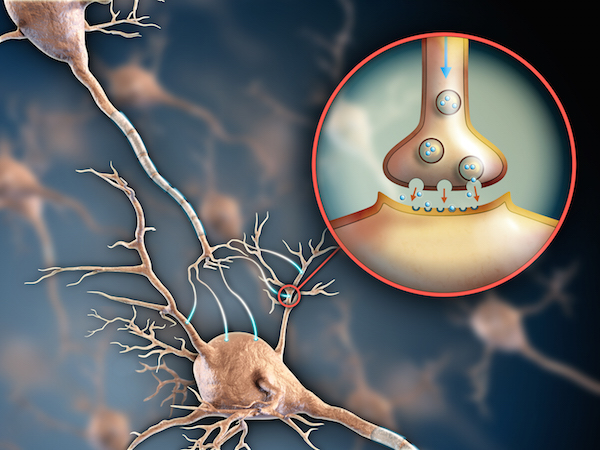

Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), also known as the drug alteplase, is an approved treatment for the most common kind of stroke — ischemic stroke — in which a blood vessel that supplies blood to the brain is blocked by a blood clot. The three-hour post-stroke time limit was set because of fears that use of the clot-dissolving drug beyond that period might cause dangerous bleeding or other complications.

After the publication of two landmark studies, the American Heart Association, the American Stroke Association and the European Stroke Association revised their guidelines in October 2008 to recommend that tPA be used up to 4.5 hours after the onset of an ischemic stroke.

Since that time, the number of patients being treated this way has surged.

But despite the initial evidence, experts have been worried that using the longer time window in actual practice might result in unnecessary delays in treatment, an increase in the number of intracerebral hemorrhages and still more deaths.

“There were lots of questions and interest in following up on the change in practice,” Bonomo said.

The study authors, from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, revisited data on 23,942 patients who had participated in a clinical trial investigating the longer time window for using tPA.

By the end of 2009, three times more patients were being treated in the later time period (3 hours to 4.5 hours) than before the change but the average time from admission to treatment stayed the same, at 65 minutes.

Patients treated in the outer time limit were 44 percent more likely to suffer an intracerebral hemorrhage and 26 percent more likely to die within three months. Still, the authors wrote, these increases “are minor and are outweighed by the benefit of the treatment.”

According to an accompanying “reflection and reaction” piece, this elevated risk translated into one additional hemorrhage for every 200 patients treated and one extra death for every 333 patients treated.

Alteplase is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency only for use within the three-hour limit. The accompanying editorial called for regulatory approval to ensure all patients access to the treatment.

The trial was funded partially by Boehringer Ingelheim, which makes alteplase.

More information

The American Stroke Association has more on ischemic stroke.