FRIDAY, Dec. 11 (HealthDay News) — With a growing array of choices for breast cancer treatment, researchers are now trying to pinpoint the best combination of therapies or the best order in which to give cancer drugs to patients.

In some cases, combination therapies will improve survival and sometimes the order in which therapies are given does not matter, said experts presenting new data at a Friday press briefing at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“The most dramatic finding [presented at the briefing] is that continuing Herceptin therapy after tumor progression improves survival,” said moderator Dr. Edith Perez, director of the Breast Cancer Program at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. “It is the first time this has been shown.”

In that study, Dr. Kimberly Blackwell, director of the Clinical Trials Program in Breast Cancer at Duke University Medical Center, reported that combining the drug lapatinib (Tykerb) with trastuzumab (Herceptin) was better than single-drug therapy in women who have HER2-positive breast cancer that has spread.

Cancers that are HER2-positive test positive for a protein called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, which fuels cancer cell growth.

Tykerb inhibits HER2 and the receptor, while Herceptin binds to the HER2 protein — a kind of double-punch, the researcher explained.

Blackwell reported on 296 women with breast cancer that had spread. Half got the drug Tykerb, 1,500 milligrams a day; the other half got 1,000 milligrams of Tykerb a day plus the Herceptin at a dose geared to their body weight.

The women’s tumors had already progressed while on a number of other treatments, so they were running out of options.

The findings? “There was significant improvement in overall survival in favor of the combination of lapatinib and trastuzumab compared to the single agent lapatinib,” Blackwell said. There was a 26 percent reduction in the risk of death if both agents were used.

Put in more human terms, that means that “15 more out of 100 women are alive at a year because of combination therapy.”

In another report, Dr. Daniel Rea, senior lecturer in medical oncology at the University of Birmingham in the UK, compared two approaches for postmenopausal women with early stage hormone-sensitive breast cancer. In the trial, 9,775 postmenopausal women with hormone-positive (the most common type) early breast cancer were assigned to get the drug exemestane (Aromasin) at 25 milligrams a day or tamoxifen at 20 milligrams a day. That was in 2001, and in 2004 the researchers assigned all the women who were getting tamoxifen to switch to Aromasin after 2.5 or three years.

Another 2,500 patients were enrolled and assigned to get either Aromasin or tamoxifen followed by Aromasin.

“The outcome is identical,” Rea said. At five years, there was 85 percent disease-free survival in both groups.

“Both of these strategies appear to be reasonable approaches for those with early cancer,” he said.

Perez said the additional option to choose between the drugs may be of special interest to patients because of the cost savings. Aromasin typically costs more than tamoxifen, she said. Tamoxifen is now available as a generic drug.

Blackwell received honorariums from GlaxoSmithKline (which makes Tykerb) and Genentech (which makes Herceptin) to conduct the study; Rea reports research funding from Novartis and Pfizer.

More information

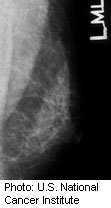

To learn more about aromatase inhibitors, head to the U.S. National Cancer Institute.