THURSDAY, Feb. 20, 2014 (HealthDay News) — A surge in the number of thyroid cancer cases in recent decades suggests the disease is being overdiagnosed and overtreated, a new study contends.

Although the number of thyroid cancer diagnoses has almost tripled since 1975, most are the more common and less aggressive form of the disease known as papillary thyroid cancer, the study authors said.

“The incidence of thyroid cancer is at epidemic proportions, but it doesn’t look like an epidemic of disease, it looks like an epidemic of diagnosis,” said lead researcher Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, a professor of medicine at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

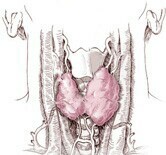

According to Welch, more people are having their neck imaged to look for blockage of the arteries or for other reasons, and nodules on the thyroid are then found.

“This means that a lot of people are having their thyroids removed for a cancer that was never going to bother them,” he said.

Welch believes that thyroid cancer should be treated much like prostate cancer, another slow-growing cancer, where patients have an option for watchful waiting that may never result in aggressive treatment.

“We have to be really cautious that we don’t create more problems than we solve. We will be looking hard at the question of watchful waiting for small papillary thyroid cancers, and we are going to be asking hard questions about whether we should even be looking for them,” Welch said.

The report was published online Feb. 20 in the journal JAMA Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery.

Dr. David Cooper, a professor of medicine and radiology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, thinks another factor may be at play with thyroid cancer diagnoses and treatment.

“I would submit that this is not the cause of the current thyroid cancer epidemic, since this is how doctors have been examining patients for decades or even centuries,” he said.

“Once a thyroid abnormality is found, it is hard to ignore it in the current medical environment, and patients often end up on an unstoppable juggernaut, leading to invasive procedures such as thyroid biopsy and ultimately to surgery,” Cooper said.

Welch noted that the treatment of many cancers is changing.

“Medicine is in the midst of a course correction. We’ve believed for years that the best strategy for cancer was to find as much as we could, but we are realizing that the population harbors a lot of early cancer, and we have to make sure we don’t create more problems than we solve by looking for them,” he said.

For the study, Welch and his colleague, Dr. Louise Davies of the VA Medical Center in White River Junction, Vt., used federal government data to study patients diagnosed with thyroid cancer from 1975 to 2009.

The investigators found that since 1975, the incidence of thyroid cancer has almost tripled, from 4.9 to 14.3 cases per 100,000 people. Nearly all of this increase has been of papillary thyroid cancer — from 3.4 to 12.5 per 100,000 people.

The biggest increase was seen among women — from 6.5 to 21.4 cases per 100,000 women. That’s nearly four times more than it is for men, which went from 3.1 to 6.9 cases per 100,000 men, the researchers noted.

Although the number of thyroid cancers diagnosed has increased dramatically, the death rate from the disease hasn’t changed, remaining at about 0.5 deaths per 100,000 people, the researchers added.

Commenting on the study, Dr. Brian Burkey, an otolaryngologist at the Cleveland Clinic, said: “We are seeing a lot more thyroid cancer, but not deaths. Most of these cancers have 95 percent cure rates. But perhaps in certain cancers we are treating it too aggressively.”

Burkey said current treatment calls for a biopsy of thyroid nodules, which can lead to removing the thyroid. “There is really only one treatment for papillary thyroid cancer — surgery,” he said.

After the thyroid is removed, patients have to take medication to replace thyroxine and triiodothyronine, the hormones produced by the thyroid.

“The question is, ‘Do we need to treat all these thyroid cancers?'” Burkey said. There is mounting evidence that watchful waiting might be a good alternative, but it’s too early to start using this as a standard treatment. That will have to wait until there are clinical trials that prove this is a good option, he explained.

Cooper added, “Until we learn to accept small thyroid cancers as less worrisome than we now consider them to be and educate our patients about the non-lethal nature of the disease, the upward trend in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment will continue.”

More information

Visit the U.S. National Cancer Institute for more on thyroid cancer.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.