WEDNESDAY, Sept. 4 (HealthDay News) — A specially designed video game may help sharpen mental skills that fade with age, a new study shows.

The study, which is published in the Sept. 5 issue of the journal Nature, tested a video game that was created by brain scientists and dubbed NeuroRacer.

The game requires players to multitask, or juggle several things that require attention at the same time.

People had to keep a car centered in its lane and moving at a certain speed while they also tried to quickly and correctly identify signs that flashed onto the screen, distracting them from their driving.

In a series of related experiments, researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, showed that the ability to multitask suffers with age. But healthy seniors who regularly played the game were able to turn back the clock. After a month of practice, they were able to multitask even more effectively, on average, than younger adults.

The study suggests that the value of video games might extend beyond entertainment. Experts say video games may not only stave off the mental deficits that come with age, but could also help in the diagnosis and treatment of mental problems.

“I think people are soon going to use video games to collect data and to train [the brain],” said Dr. John Krakauer, director of the Brain, Learning, Animation and Movement Lab at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “I think it’s very promising. I think it’s going to happen.”

The study was conducted in healthy adults who were able to think and remember normally for their age. But researchers have already begun to test NeuroRacer to see if it might benefit people with ADHD or depression, two conditions that hamper the ability to pay attention and stay on task.

They said they’re also developing four other games that will challenge different mental skills.

These games aren’t likely to be sold in stores, but if further testing proves them to be valuable, researchers think they may one day make their way to doctors’ offices.

“It would be a medical diagnostic and therapeutic, potentially even going the route of FDA approval,” Dr. Adam Gazzaley, director of the Neuroscience Imaging Center at the University of California, San Francisco, said during a Tuesday news conference on the findings. Gazzaley is a co-founder of the company that is developing the next generation of the video game. The study was funded by Health Games Research, a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the U.S. National Institute on Aging.

For the research, scientists recruited 174 healthy adults aged 20 to 80. About 30 people from each decade of life were asked to play the NeuroRacer game to see how well they were able to multitask. These first tests showed that the ability to multitask gets worse with age. Adults in their 20s saw a 28 percent drop in performance when they were doing two things at once, while those in their 30s saw their performance drop about 39 percent.

Next, they wanted to see whether people could get better at multitasking with practice. For these experiments, they picked 46 healthy seniors who were between the ages of 60 and 85 and assigned them to one of three groups: 16 were asked to play the NeuroRacer game for an hour a day three times a week, 15 played a version of the game that required them to do only a single task at a time and 15 others didn’t play the game at all.

After a month, seniors who had practiced multitasking with NeuroRacer showed big gains compared to their peers in the other two groups.

The drop in performance that everyone experiences when they try to do two things at once “improved dramatically from 65 percent to 16 percent, and even reached a level better than 20-year-olds,” who had only played the game once, Gazzaley said.

What’s more, seniors who played for an hour a day three days a week saw improvements in other mental skills that weren’t directly trained by the game. Working memory, or “the ability to hold information in mind, as people do when they’re participating in a conversation and they have to think about what they want to say and remember it while they wait their turn to speak” got better, Gazzaley said, as did their visual attention (the ability to sustain focus on a task in a boring environment).

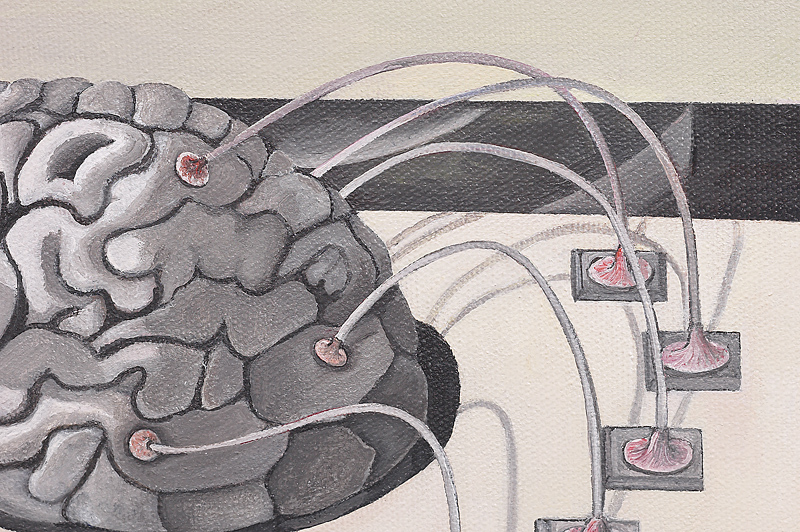

Additional tests, which measured the brain’s electrical activity, showed a boost in areas responsible for cognitive control, the skill that helps the brain switch back and forth between activities.

The improvements in mental function lasted for about six months after seniors stopped playing, the researchers said.

What remains to be seen, experts said, is whether these improvements will help people in real life.

“They could argue that if you got better at this game then maybe you would be a safer driver when you’re elderly,” Krakauer said. “You may be able to look for what exit you need to take and stick to the road.”

“[But] they haven’t tested that,” he said. “We don’t know the answer to that.”

The researchers agreed.

“In order to see improvement in daily life, you need larger numbers of people” who are studied for a longer period of time, Gazzaley said. Planning for those studies is currently in the works.

More information

For more ways to prevent aging, visit the U.S. National Institute on Aging.

Copyright © 2024 HealthDay. All rights reserved.