FRIDAY, Sept. 7 (HealthDay News) — A little shyness in young children can be endearing. But new research suggests that preschoolers who are extremely socially reserved and withdrawn may be at risk for falling behind in math and reading when they start kindergarten.

The study, published online recently in the Journal of School Psychology, suggests that super-shy kids may be at more risk than their active, overactive and outgoing peers. Children showing shy and withdrawn behavior early in the school year began with lower academic skills than other students and showed the slowest gains in learning skills over time.

Shy kids may fall into the background of the average preschool classroom, making it more likely teachers will fail to identify their unique learning needs, said study author Rebecca Bulotsky-Shearer, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Miami. “Engagement is important in learning, especially in early childhood education. If there is a child who needs that extra support and is being missed, it’s easier to fall behind the others,” she explained.

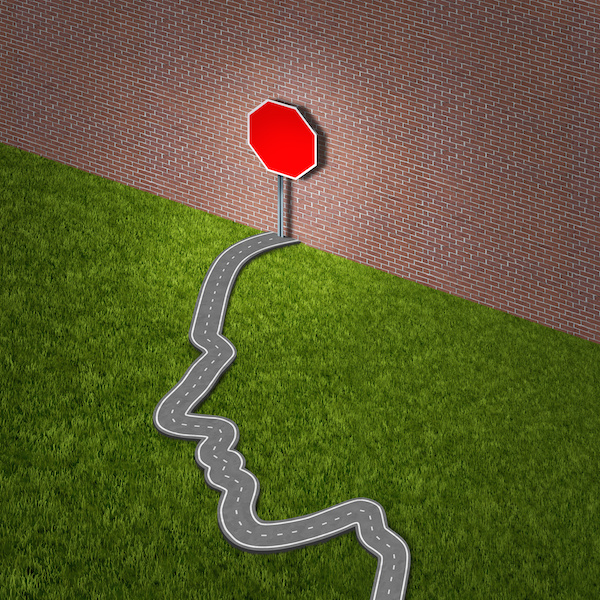

The research suggests that feeling withdrawn may trigger a cascade of learning problems in the preschooler. “There may be different learning trajectories for kids if they are shy,” Bulotsky-Shearer said.

For some children, the shyness may be a sign of another problem causing the inability to get actively involved in classroom activities with other children. “Some shyness is unhealthy, creating a high degree of anxiety,” she said.

The study looked at the social and academic progress of children aged 3 to 5 throughout the school year, following over 4,400 pre-kindergarten children in the Head Start program in a large northeastern urban school district. The majority of participants were black (71 percent), with the remaining children Hispanic (16 percent), white (7 percent) and Asian or other (5 percent).

Most children were from homes with an annual income below $15,000. The participants came from 268 mixed-age classrooms in 100 different centers. Teachers assessed the emotional and academic progress of each child three times during the school year. To assess the non-academic behavior, they used a six-point scale that ranged from well-adjusted to extremely socially and academically disengaged.

Older children and girls tended to be better adjusted in class, showed fewer behavioral problems and exhibited higher levels of language and math skills, the data showed.

The research has limitations, said Dr. Andrew Adesman, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York. “There’s a chicken-and-the-egg phenomenon: If there are children who are academically weak, they may be inhibited in a learning situation and then seem shy.”

Adesman also questioned whether the lack of ethnic and socio-economic diversity in the study makes the research less applicable to the population as a whole. Too, he wondered whether the mixed-age classroom, including kids just starting preschool and others ready for kindergarten, could be skewing the results.

“For example, some 3-year-olds have separation issues and may be anxious in a preschool setting,” he said. “After all, even if you put a high school freshman in a class with seniors, the freshman is going to be a little withdrawn.”

To help ensure all kids — the shy and the not-so-shy — get the attention they need, Bulotsky-Shearer recommended parents check in with teachers regularly to see how their children are doing, both academically and socially, especially when their kids are young. “Everybody should ask how their kid does within the group,” she said.

Adesman encouraged parents to realize that many kids who are considered shy do just fine. “The greatest risk is in a very small number of children,” he said. “Be aware that sometimes troublemakers will get the teacher’s attention, but teachers and parents need to be mindful that some children suffer silently and there may be some risk of academic difficulty in kids with significant social withdrawal.”

While the study found an association between extreme shyness and possible learning problems, it didn’t demonstrate a definitive link.

More information

Learn more about child development from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University.