THURSDAY, Jan. 21, 2016 (HealthDay News) — As cases of the mosquito-borne Zika virus are spreading across central and South America and the Caribbean, experts say it’s only a matter of time before the disease, which has been linked to an alarming increase in birth defects in Brazil, is transmitted within the United States.

“It’s not if, it’s when,” said Mustapha Debboun, director of the mosquito control division at Harris County Public Health and Environmental Services in Houston.

Travelers to Zika-affected countries will bring the virus back to the United States, he said, “and sooner or later, the mosquitoes will pick up the virus.”

Last Friday, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took the unusual step of warning pregnant women and women who want to become pregnant to avoid travel in 14 countries and territories where Zika transmission is ongoing.

The list, to date, includes Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, Venezuela and Puerto Rico.

On Tuesday, the CDC issued interim guidance to doctors on managing pregnant women returning to the United States from areas with Zika transmission. Obstetricians and other health professionals should ask all pregnant women about their recent travels in the affected areas and test for Zika in those with fever, rash, muscle aches or pink eye during or within two weeks of travel, the CDC said.

The CDC’s warning coincides with reports that nearly 3,900 babies in Brazil have been born in the last year with microcephaly, a birth defect resulting in an abnormally small head that can cause developmental issues and even death.

The Zika virus’ impact on unborn babies remains somewhat of a mystery. Studies are underway to assess its association with microcephaly and other poor outcomes, the CDC said.

Dr. Edward McCabe is senior vice president and chief medical officer of the March of Dimes, a nonprofit group that works to improve the health of mothers and babies. “I think this is concerning. We need to take it seriously,” he said.

Currently, there’s no vaccine to prevent the virus. And developing one could take years, said McCabe, whose organization started following the Zika virus several weeks ago, when the association with microcephaly in Brazil first came to light.

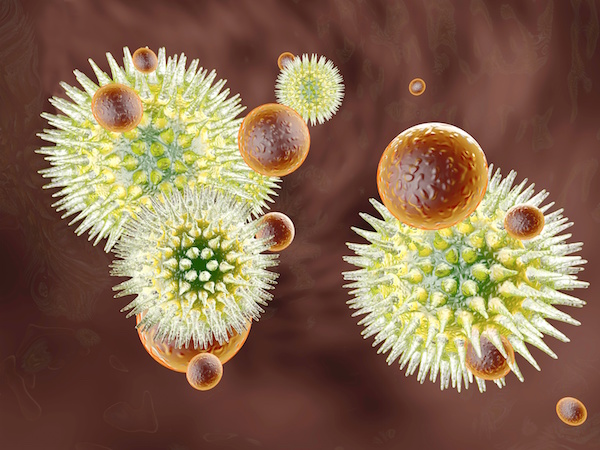

Zika transmission occurs when the Aedes aegypti mosquito takes a blood meal from a person who is infected and passes the virus along while feeding on another person.

U.S. infections reported in recent days — one each in Texas and Hawaii, two in Illinois and three in Florida — involved individuals who had traveled to countries where the virus is endemic.

The Hawaii State Health Department last week announced that a baby born in an Oahu hospital with microcephaly tested positive for a past Zika infection. The newborn likely acquired the virus from the mother, who was living in Brazil in May 2015, officials said.

But the CDC and other experts say Zika transmission within the United States is inevitable.

“With the recent outbreaks in the Pacific Islands and South America, the number of Zika cases among travelers visiting or returning to the United States will likely increase,” the CDC noted in comments accompanying a global map of Zika virus transmission. “These imported cases may result in local spread of the virus in some areas of the United States,” the agency cautioned.

How quickly the virus may begin spreading locally is a matter of speculation.

“There’s a good chance we’ll see it this coming summer, given what we saw with chikungunya two years ago,” said Dawn Wesson, an associate professor of tropical medicine at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, in New Orleans.

Chikungunya is another mosquito-borne illness that spread rapidly in the Caribbean and Central America before popping up in 2014 among non-travelers in Florida.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito prefers warmer climates, making certain areas of the United States more vulnerable to home-grown cases.

“I think that the southern Gulf Coast, South Florida and Southern California are probably all at risk for introduction, and Hawaii,” Wesson said.

Experts say there’s a lot people can do to protect themselves from mosquito bites, including removing any standing water from containers where mosquitoes breed. Other protective measures include liberally applying insect repellent and wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants.

“We have to be alert, we have to be aware. But we don’t have to be alarmists,” Debboun said.

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more about the Zika virus.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.