WEDNESDAY, April 13, 2016 (HealthDay News) — Zika virus is a definite and direct cause of microcephaly and other brain-related birth defects, U.S. health officials announced Wednesday.

“It is now clear,” Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said at a midday media briefing. “The CDC has concluded that Zika does cause microcephaly.”

“There is still a lot that we don’t know, but there is no longer any doubt that Zika causes microcephaly,” Frieden added.

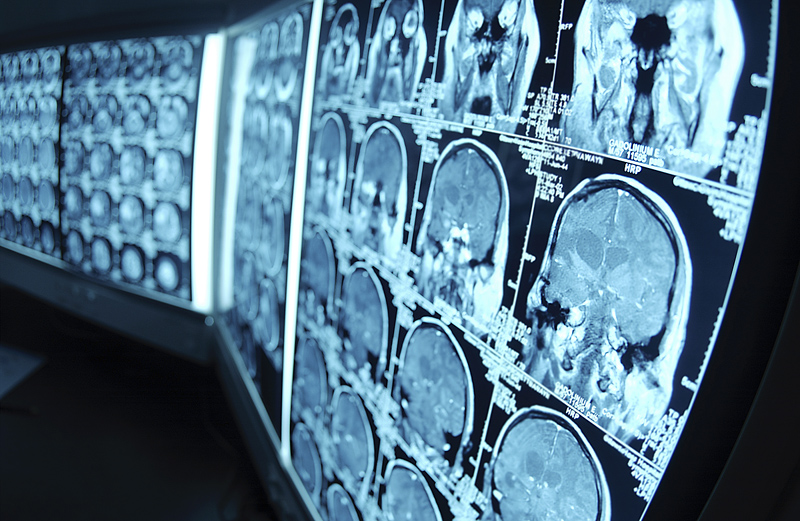

What’s more, it appears that the mosquito-borne Zika virus causes a particularly severe form of microcephaly that does terrible damage to infants’ brains, said Dr. Sonja Rasmussen, director of the CDC’s Division of Public Health Information and Dissemination.

The CDC made its announcement following what it described as a painstaking evidence review led by Rasmussen that was published on an expedited basis on Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, Frieden said.

“This study marks a turning point in the Zika outbreak,” he said.

Until now, the CDC had said Zika appeared to be associated with microcephaly, which results in an unusually small head and brain, but had been careful not to draw a direct causal link between the virus and the birth defect.

That’s because “this is an unprecedented association” between a mosquito-born virus and a horrifying birth defect, Frieden explained, and the agency wanted to proceed with caution.

“Never before in history has there been the situation where a bite from a mosquito could result in a devastating malformation,” Frieden said.

However, there’s still much that needs to be learned about Zika’s effect on fetal development, said Rasmussen, who’s also editor-in-chief of the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

For example, no one knows the exact risk of brain-related birth defects to the baby of a mother infected with Zika, she said, because some Zika-infected women have given birth to apparently healthy babies.

“We don’t know if the risk is somewhere in the range of 1 percent or in the range of 30 percent,” she said. “That’s one of the key questions we really want to answer.”

Researchers also don’t know if Zika will wind up causing learning disabilities to these apparently healthy children later in life, or if Zika also causes birth defects beyond those that are brain-related, Rasmussen added.

The CDC completed its work on the evidence review days ago, and as recently as Sunday was still working with the NEJM on revisions that would incorporate the latest scientific evidence, Rasmussen said.

Rasmussen said the CDC concluded that Zika causes microcephaly based on a checklist of specific criteria that included:

- Women who deliver babies with microcephaly were infected with Zika during the first and second trimester of gestation.

- A consistent pattern has developed where pregnant women infected with Zika have given birth to children with microcephaly and other brain-related defects.

- The link makes sense biologically, with autopsies revealing the presence of Zika in the brains of babies with severe microcephaly who died.

The agency submitted its research to the NEJM for peer review because “we didn’t want this to just be something that was coming from the CDC,” Rasmussen said. “We wanted this to be something that was representing the public health community.”

The CDC’s declaration of a direct link is a stronger stance than that taken by the World Health Organization, which in its latest report cited a “scientific consensus that Zika virus is a cause of microcephaly.”

Nevertheless, Rasmussen said the CDC’s conclusion is consistent with the WHO’s approach to Zika.

“I think we are on the same page with them,” she said.

The CDC hopes that its findings will prompt pregnant women and women of child-bearing age to be even more careful regarding Zika, Rasmussen said.

Pregnant women should not travel to areas where Zika is being actively transmitted by mosquitoes, she said.

To date, most of the infections have occurred in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Women living in an active Zika region should protect themselves by wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, staying indoors with window and door screens to keep mosquitoes out, and using insect repellants.

People also can help cut down on mosquitoes in their neighborhoods by policing their properties and getting rid of any sources of standing water, she said.

“Mosquitoes breed in standing water, especially these mosquitoes,” Rasmussen said. “Even small amounts of standing water.”

As of April 6, there were 700 confirmed cases of Zika in U.S. states and territories, according to the CDC. However, none of the cases in the continental United States have occurred due to local transmission of the virus via mosquito bite. Nearly all these infections were acquired while traveling outside the country.

Public health officials expect Zika to become active in the United States with the onset of mosquito season in the spring and early summer. The Aedes aegypti mosquito is expected to be the primary carrier in the United States.

Florida, Texas and Hawaii are the states most at risk for local transmission of Zika, CDC officials have said. However, the A. aegypti mosquito ranges as far north as San Francisco, Kansas City and New York City, although health officials have said infections that far north are unlikely.

More information

For more on Zika virus, visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To see the CDC list of sites where Zika virus is active and may pose a threat to pregnant women, click here.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.