TUESDAY, Aug. 30 (HealthDay News) — Using bones retrieved from London’s medieval graveyards, scientists have isolated the strain of bacteria thought to be responsible for the Black Death, and determined that it is most likely now extinct.

The plague, caused by a strain of flea-borne bacteria called Yersinia pestis, ravaged Europe close to seven centuries ago. But the variant of the bacterium behind that scourge is different from the modern strain that still causes about 2,000 new cases of bubonic and pneumonic plague each year, researchers said.

The new research also confirms Y. pestis as the culprit behind the medieval outbreak, the study authors said.

“The controversy as to what caused the Black Death is now resolved,” said study co-author Hendrik Poinar, associate professor in the department of anthropology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. “It clearly was the bacterium Yersinia pestis that was responsible for 30 million deaths some 660 years ago.”

Poinar and colleagues from the United States, Germany, and Britain discuss their findings in the Aug. 29 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

By it’s conclusion, the Black Death outbreak (1347-1351)was responsible for killing off about one-third of Europe’s population.

A subsequent 19th century pandemic involving Y. pestis took the lives of roughly 12 million Chinese. And the threat has endured: in the 21st century about 10 to 20 Americans (and more than 2,000 people worldwide) will develop plague each year. Fortunately, experts note that the germ is susceptible to antibiotics so the disease is not as deadly as it once was.

For the new study, the researchers turned to skeletal remains retrieved from the East Smithfield mass burial site in London. The plot is one of only several in the world that archeologists have conclusively linked to the 14th century pandemic.

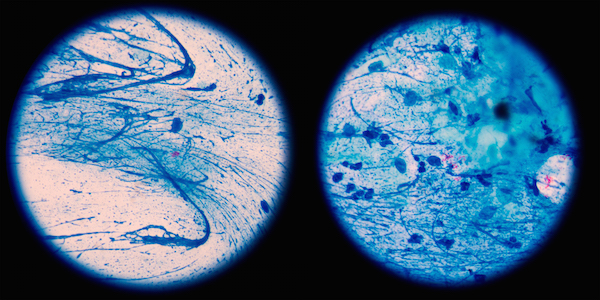

In all, 109 skeletal remains (derived from Black Death patients buried between 1348 and 1350) underwent comprehensive DNA sequencing. In the end, the team used a new “targeted DNA capture approach” to construct what they say is the “longest contiguous genomic sequence for an ancient pathogen to date.”

Comparing the 14th century bacterium against 21st century examples, the investigators reached a definitive conclusion: the two strains are not the same.

What’s more, as the medieval bacterium does not match any strains of Y. pestis currently known to be at large, the researchers concluded that the potentially more virulent ancient strain of the bacterium no longer exists.

“Bacteria can mutate over time,” explained Dr. Pascal James Imperato, chair of the department of preventive medicine and community health at the State University of New York (SUNY) Downstate Medical Center in New York City. “They have found that the DNA of this ancient bacteria does not exactly match what we have today. Which means we could be dealing with two very different types of organisms.

“This information informs us about transformations that can take place in microorganisms over time,” Imperato added. “And that those transformations have a direct bearing on the capability of an organism to cause more or less serious clinical illness, and its ability to be transmitted more efficiently or less efficiently.”

Dr. Philip Tierno, director of clinical microbiology and immunology at New York University Langone Medical Center in New York City, agreed.

“Insight into the evolutionary process can be helpful, because you can see what the virulent factors were that actually killed people,” he said. “This type of investigation does have value, in that it can potentially highlight what’s most lethal about the bacterium now at hand.”

Poinar noted that the technology his team used to analyze the centuries-old Y. pestis may help humans fight pathogens today. “This will allow us to assess why they were so virulent in the past, and be better prepared should they re-emerge,” he said.

More information

For more on the plague, visit the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.