TUESDAY, April 23 (HealthDay News) — Long-term exposure to air pollution may speed up the process of atherosclerosis, also known as hardening of the arteries, a new study suggests.

Although this exposure to higher concentrations of air pollution could increase people’s risk for heart attacks and stroke, the researchers noted that reductions in air pollution could have the opposite effect.

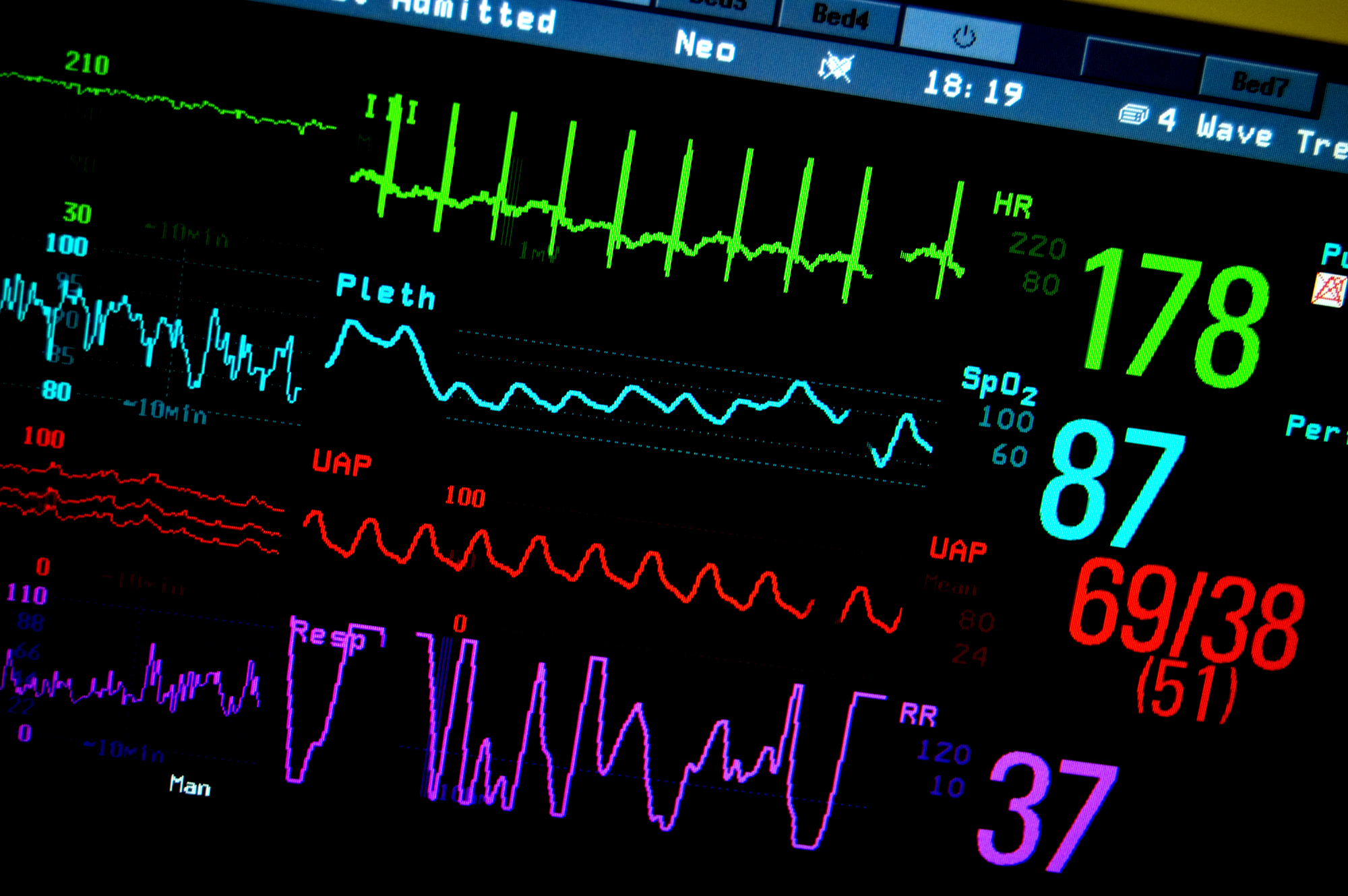

The study involved nearly 5,400 people between the ages of 45 and 84 in six different U.S. cities who did not have heart disease. The researchers examined the air pollution levels at each of their homes, and then compared the levels to ultrasound measurements of their blood vessels taken at least three years apart.

After taking other risk factors, such as smoking, into account, the researchers found that, on average, the thickness of the carotid artery increased by 0.014 millimeters each year.

Thickening of the inner two layers of this key blood vessel, which supplies blood to the head, neck and brain, occurred more quickly following exposure to higher concentrations of fine particulate air pollution. The researchers said the thickness of the carotid artery is an indicator of how much atherosclerosis is present in the arteries throughout the body.

“Our findings help us to understand how it is that exposures to air pollution may cause the increases in heart attacks and strokes observed by other studies,” study leader Sara Adar, the John Searle Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, said in a news release.

On the other hand, the study revealed that reductions in fine particulate air pollution can help slow the thickening of the carotid artery.

“Linking these findings with other results from the same population suggests that persons living in a more polluted part of town may have a 2 percent higher risk of stroke as compared to people in a less polluted part of the same metropolitan area,” Adar said in the news release.

“If confirmed by future analyses … these findings will help to explain associations between long-term [small particle] concentrations and clinical cardiovascular events,” the study’s authors wrote.

In response to the findings, Nino Kuenzli, of the University of Basel in Switzerland, said in a news release that the study “further supports an old request to policy makers — namely that clean air standards ought to comply at least with the science-based levels proposed by the World Health Organization.”

The study was published online April 23 in the journal PLoS Medicine.

More information

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency provides more information on the link between air pollution and heart health.