TUESDAY, Jan. 11 (HealthDay News) — Nearly two-thirds of men who have prostate cancer surgery experience urinary incontinence afterward, but new research suggests that behavioral therapy can help lessen bladder control problems for a significant number of them.

After eight weeks of behavioral therapy — including fluid management, pelvic exercises and bladder control techniques — the researchers found a 55 percent reduction in incontinence episodes.

“Behavioral therapy is one more option for men,” said study author Dr. Patricia S. Good, a professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “It’s not a perfect treatment, and it does require work, but it also provides a significant improvement in quality of life.”

The findings are reported in the Jan. 12 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

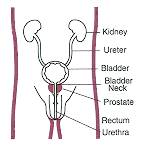

Over a lifetime, about one in six men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. One treatment option, called a radical prostatectomy, includes removing the prostate gland and surrounding tissue as well as the seminal vesicles, according to the U.S. National Cancer Institute. And, though the surgery has been proven effective for removing the cancer, it can cause serious side effects, including long-lasting urinary incontinence in as many as 65 percent of the men who undergo the surgery, according to the researchers.

An additional surgical intervention is available to help with urinary incontinence, but many men who’ve already gone through cancer surgery are reluctant to have another surgical procedure, they point out.

Other options that might help with incontinence include behavioral therapy, biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation. To see which of these alternatives might be helpful, Goode and her colleagues recruited a group of 208 men, 51 to 84 years old, who were experiencing urinary incontinence a year or more after having had prostate cancer surgery.

The men were randomly assigned to one of three groups. One group participated in eight weeks of behavioral therapy, another group had behavioral therapy plus biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation and the third group was given no additional treatment and served as the control group. The men were asked to keep bladder diaries throughout the study.

Behavioral therapy, which included four home visits, about one every two weeks, involved instruction in pelvic floor exercises, pelvic muscle contraction and daily exercises, such as deliberately stopping the flow of urine. they also practiced urge control, which meant delaying a visit to the toilet and using pelvic floor contractions to avoid an accident. Men in this group were instructed to drink eight ounces of beverages six to eight times a day, spaced throughout the day. They were advised to avoid caffeine.

The second group received this training and, in addition, was given in-office biofeedback training and daily at-home pelvic floor electrical stimulation, according to the study.

After eight weeks, the researchers found that the average number of incontinence episodes dropped from 28 to 13 a week, a 55 percent decline, for the men in the behavioral therapy group, and from 26 to 12 episodes a week, down 51 percent, for men who’d had biofeedback and electrical stimulation as well as behavioral therapy. The control group had a 24 percent reduction, on average, in incontinence episodes.

The reductions in incontinence lasted at least 12 months, the study found.

“We were very pleased,” Goode said. “And, the men who decreased their accidents by half were thrilled.”

Not everyone is convinced, however, that behavioral therapy is the best option.

“For patients with incontinence, especially bad incontinence, behavioral therapy might not be worth the time,” said Dr. David Penson, professor of urological surgery and director of surgical quality and outcomes at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. “I don’t think the bang is worth the buck.”

“For men with a little bit of post-prostatectomy incontinence, behavioral therapy isn’t a bad option if you’re averse to having another surgery,” said Penson, who authored an editorial on the study in the same issue of the journal. “Behavioral therapy works, but don’t expect too much.”

For many men, he added, an even better option might be to wait to have surgery and monitor this often slow-growing cancer through PSA, or prostate-specific antigen, test surveillance. PSA testing measures the level in the blood of this protein, which is considered a biological marker of prostate cancer.

“Can’t we consider the idea of watching these patients for a bit?” Penson asked. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

More information

The U.S. National Cancer Institute has more about treating prostate cancer.