TUESDAY, Jan. 18 (HealthDay News) — Stents, already used to open clogged heart arteries, might have another use: clearing arterial blockages in the brain after traditional stroke treatments fail.

In new research involving 19 stroke patients, doctors say this experimental application appears nearly full-proof in unblocking brain arteries in patients for whom other clot-removal methods didn’t work.

“The bottom line is that stroke is a deadly condition,” said study lead author Dr. Italo Linfante, director of endovascular neurosurgery and interventional neuroradiology at the Baptist Cardiac and Vascular Institute in Miami. “Up to 10 years ago it was a death sentence. Yet now if you go to the hospital early enough with a stroke there are several ways to be treated.”

Current treatments are 60 percent successful, he noted, “so we are always looking to develop better and better weapons, and pushing the limits to fix it. And with stents we are reaching 95 percent, in terms of successfully opening up the arteries.”

Linfante and his team are slated to present their findings this week in Miami at the International Symposium on Endovascular Therapy (ISET).

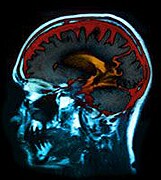

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States today. Ischemic strokes, caused by blood clots, are the more common type of stroke. Hemorrhagic stroke, the other type, occurs when a blood vessel ruptures and bleeds into the brain.

Before participating in the study, none of the patients had benefited from standard treatments used to remove arterial blockages in the brain. These blockages reduce normal blood flow and raise the risk for death and disability. Standard treatments range from clot-dissolving drugs to procedures aimed at suctioning out blockages.

By inserting stents — tiny metal mesh tubes — into blocked cranial arteries, the study team was able to open up arterial passages in 18 of the 19 patients, amounting to a 95 percent success rate.

Twelve of the patients (63 percent) had minimal or no side effects, and five patients (26 percent) ultimately died from a major stroke, according to the researchers.

Yet they concluded that 80 percent to 90 percent of the stroke patients would have become severely disabled and/or died if such stents had not been used to restore normal blood flow.

Linfante said that while the results of his investigation must be viewed as preliminary, he’s “very confident” that further research will prove that stents are an effective intervention for stroke patients. Clinical trials are needed, he said.

“In the U.S. today, stents are only FDA-approved for use in the heart,” he added. “But so far, the results with stroke patients are unbelievably positive.” Stents for stroke have already been tested in clinical trials in Europe, he explained, noting that “they have seen the same success we have seen.”

So, Linfante said, “here we’re trying to move ahead as quickly as possible to do more research using them with stroke patients in large clinical trials. And we hope that, for the general public, we will see it approved for this use within the next two or three years.”

Dr. Richard B. Libman is chief of the division of vascular neurology with the Harvey Cushing Institutes of Neuroscience at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System in Great Neck, N.Y. He called the new findings “extremely encouraging” but also urged caution.

“There have been similar small studies already published giving quite similar results,” he noted. “But they all involve a very small series of patients, which makes it a little hard to interpret. Not only that, but there is no comparison control group. And that’s one of the weaknesses of all device trials in stroke that have been published so far, because the FDA does not have the same stringent requirements for the approval of mechanical devices as they do for medications.”

“Having said that, this type of approach is innovative, aggressive, and very promising,” Libman added, “and definitely demonstrates the need for large trials with an appropriate control group if possible.”

It should be noted that studies presented at meetings typically do not undergo the rigorous checks that precede publication in scientific journals.

In a second study, also slated for presentation at the ISET meeting, researchers from the Stanford University School of Medicine report that drug-coated stents may provide long-term relief for patients with clogged leg arteries typical of peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Two years after stents coated with the drug paclitaxel were inserted in nearly 280 patients, the investigators found that three-quarters of the leg arteries remained open, and the post-procedure survival rate among such patients approached 87 percent. Compared with bare-metal stents, the drug-coated stents performed significantly better in this regard, the researchers found.

More information

For more on stents, visit the American Heart Association.