FRIDAY, March 28, 2014 (HealthDay News) — A tiny spinal fracture can turn an active person into a shut-in. Until now, patients with these compression fractures have had limited options, but a new procedure shows promise, researchers say.

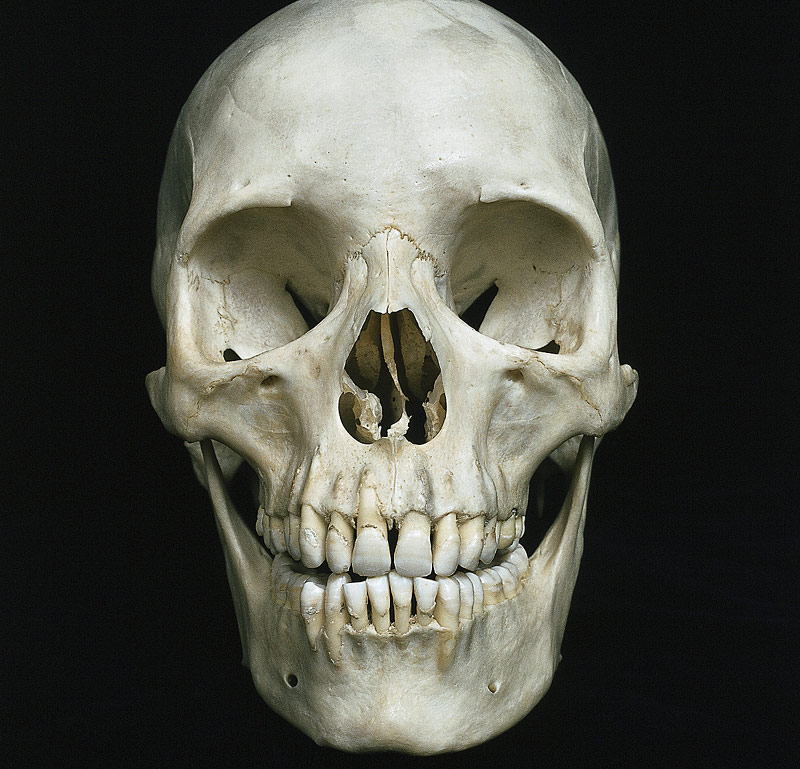

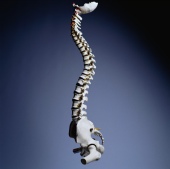

Vertebral or compression fractures — micro-breaks in the building blocks of the back typically caused by bone-thinning osteoporosis — affect about 700,000 people in the United States every year. They often lead to severe pain and disability.

“These fractures can turn an 80-year-old grandmother who likes to garden and bike ride into someone who is stuck in the house and stuck on narcotics,” said Dr. Sean Tutton, lead author of a study scheduled for presentation this week at the annual meeting of the Society of Interventional Radiology in San Diego.

“It’s been my experience that if we don’t do something early on, these people can deteriorate,” said Tutton, a professor of radiology, medicine and surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Tutton’s study of a treatment approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in January suggests that a small polymer implant in the back might provide similar pain relief and improvement of function when compared to established procedures, potentially with fewer downsides.

In a compression fracture, all or part of a spine bone collapses. Most people are unaware how or when they fractured the bone; they just begin to feel pain, Tutton said.

Compression fractures, if untreated, can lead to curvature of the spine, which can impair balance and overall activity levels. Patients with compression fractures tend to gain weight, lose muscle mass, get pneumonia and generally go downhill, Tutton said.

The implant provides a type of scaffolding for the affected spine bone, including a reservoir to direct and contain bone cement for added support, Tutton explained. It is approved only for the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

Two other procedures — called vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty — commonly are used for these fractures. Both involve injecting bone cement through a small hole in the skin into a fractured vertebra to provide stabilization and strength.

With all three procedures, including the new implant treatment, patients receive local anesthesia and light sedation. The procedures are guided by fluoroscopic X-ray and typically are done on an outpatient basis, Tutton said.

Complications of standard treatments include leakage of the cement and fracture of the adjacent bones, said Dr. Mark Raden, chairman of radiology and chief of neuroradiology at Staten Island University Hospital in New York City.

It’s recommended that patients try conservative therapy — rest and treatment of the pain — before opting for a treatment procedure, Raden said. “But the longer you wait, the harder it is to fix the problem,” he said. “Some say you shouldn’t wait more than eight weeks [before seeking help with a procedure].”

The new study involved 300 patients from 21 centers in the United States, Canada, Belgium, France and Germany. People with painful vertebral compression fractures associated with osteoporosis were randomly assigned either to get the new implant or have a kyphoplasty procedure.

Participants were then assessed for pain levels, maintenance of (or improvement in) function and serious device-related issues. After a year of follow-up, no device-related complications were found among the patients who received the implant, Tutton said.

“The research showed that while the new [implant] is not necessarily better, it is not inferior,” said Raden, who was not involved with the study.

As for cost, Tutton said he thinks it will be competitive with kyphoplasty, and is less likely to leak or cause secondary fractures.

The study was sponsored by Benvenue Medical, the maker of the implant, based in Santa Clara, Calif. Tutton, in addition to serving as research coordinator for the study, provides training about the devices as a consultant to the company, he said.

Because this study was presented at a medical meeting, the data should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

More information

Learn more about compression fractures from the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.