MONDAY, Jan. 4 (HealthDay News) — Most depressed adults in the United States don’t get the minimum recommended treatment, and the vacuum is especially dramatic among minority populations.

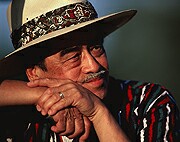

“This was very astonishing,” said Hector Gonzalez, lead author of a study in the January issue of Archives of General Psychiatry and assistant professor of family medicine and public health at Wayne State University in Detroit.

“Studies have shown over and over that about half of people with depression get treatment, but as a clinician I knew that wasn’t the case. I knew it wasn’t the case for blacks and Latinos,” continued Gonzalez, a Mexican American raised in New Mexico. “I wanted to see how many people were getting minimal standard-of-practice care.”

The answer turned out to be that only a paltry one in five U.S. adults gets guideline-recommended treatment, with the number dropping to one in 10 for Mexican Americans and African Americans.

Depression “will be the leading cause of disability in the next 20 years, so if we want a healthy nation we need to address this,” Gonzalez added.

This study draws attention to the extent to which adults, “especially ethnic and racial minorities, particularly Mexican Americans, who have major depression aren’t receiving guideline-based treatments, and this is something we’ve been aware of for a while,” said Dr. Mark Olfson, professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University/New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York City.

The authors reviewed information on 15,762 adults aged 18 and over living in the 48 contiguous states.

Although about half of depressed individuals received some kind of care, only 21.3 percent had received at least one treatment during the past year meeting American Psychiatric Association guidelines.

Whereas previous research lumped different ethnic groups into one broad category, Latinos, these researchers looked at individual subgroups, revealing that Mexican Americans, African Americans and Caribbean blacks were even less likely to receive adequate care than others.

Puerto Ricans, meanwhile, had depression care equal to or even greater than that of whites, which suggests that health care practitioners may have something to learn from this group, Gonzalez said.

Psychotherapy was more commonly prescribed than antidepressants, especially among Caribbean blacks and African Americans, a surprising finding, he said. And psychotherapy-oriented treatments were more likely to meet treatment recommendations.

“That suggests to me that maybe psychotherapies are more powerful to these disparate groups, and that maybe we could use that as a method for reducing disparities in depression care,” he said.

Health insurance and access to care — or lack thereof — did not fully explain the differences.

“This raises the issue of whether the services that are being offered attract or are culturally sensitive to some of these populations and whether people aren’t, for that reason, availing themselves of treatment,” Olfson said.

“A lot of treatment used for depression is comparatively shallow so people are receiving a visit or two of psychotherapy or might fill one prescription of an antidepressant,” he added. “To have the greatest chance of doing good, treatments have to be delivered in a more sustained and vigorous way.”

Two other studies in the same issue of the journal pointed out potentially troubling trends in U.S. mental health care. One found that more Americans are being told to take antidepressants and antipsychotic medications in tandem.

The benefits of such a course are largely unproven, while more evidence indicates there may be harmful effects, said the researchers, who were from the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and Columbia University Medical Center/New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York City.

The other study, conducted by researchers at the University of Colorado Denver and funded by Pfizer, Inc., discovered that many Medicaid patients taking second-generation antipsychotic medications such as olanzapine (Zyprexa), fluoxetine (Prozac) and risperidone (Risperdal), aren’t getting tested for blood glucose or lipid levels, despite abundant warnings that these drugs raise the risk for diabetes.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health has more on depression.