WEDNESDAY, May 14, 2014 (HealthDay News) — Preliminary research suggests that the commonly used antidepressant Celexa, and perhaps other drugs in its class, may temporarily lower levels of a protein that clogs the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s too early to know if the medication — or the drugs that are similar to it — could play a role in the prevention of the devastating brain-robbing disease. The authors of the new study only looked at the effects of a large dose of the drug for less than two days, and only healthy younger people took part in the research.

There’s another important caveat: Previous efforts to reduce the levels of the protein, known as beta amyloid, haven’t helped patients fend off Alzheimer’s. And Celexa can cause some potentially serious side effects.

Still, “this is the first step in trying to move toward a preventive treatment,” said study author Dr. Yvette Sheline, a professor of psychiatry, radiology and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, in Philadelphia. “Up until now, people have been focused on treating Alzheimer’s disease itself, but that seems to be happening too late.”

An estimated 5 million people in the United States suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, and one in three seniors will die while affected by the illness or another form of dementia, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

There’s no cure for Alzheimer’s, and the existing treatments can only provide relief of symptoms in some cases.

The new study examines the antidepressant Celexa, known by the generic name citalopram. It’s one of several antidepressants (including Paxil, Zoloft and Prozac) that are known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

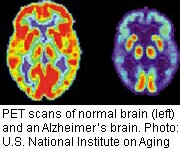

The researchers report that they were able to use the drug to significantly lower the levels of beta amyloid in older mice that were genetically modified so they’d develop an Alzheimer’s-like disease. Beta amyloid is a normal component of the brain, but its levels grow into gunk-like “plaques” in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

The study researchers also gave 60-milligram (mg) doses of the drug or an inactive placebo to healthy people aged 21 to 50. They then measured levels of beta amyloid in the spinal fluid of the participants over a 37-hour period.

Production of beta amyloid slowed by 37 percent in the participants who received Celexa, the investigators found.

In the best-case scenario, the drug would reduce levels of the protein before the levels became dangerous and send patients on the road to Alzheimer’s later in life, Sheline said.

But there are still many unanswered questions. For one, it’s not clear if the drug would have this effect in the long term. Sheline noted that’s the next step for research.

“Is that effect sustained for several weeks? We’re going to be doing that research in older people aged 65 to 85,” Sheline said. “If we show that the effect is maintained, that the beta amyloid stays lowered, then we’d do longer-term studies.”

How might the drug affect beta amyloid levels? It’s not clear, but it may disrupt their creation by affecting an enzyme associated with amyloid production, Sheline said. Would the benefit of the drug be worth Celexa’s expense and its side effects, which include headache, nausea and sexual dysfunction? That’s not clear either.

And researchers don’t know if other SSRI antidepressants would have a similar effect, although Sheline said there’s no reason to think they wouldn’t.

Dr. Anton Porsteinsson, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Care, Research and Education Program at the University of Rochester School of Medicine in New York, said Celexa seems to have a “not inconsequential” impact on levels of the protein.

But he cautioned that while Alzheimer’s researchers still tend to believe that too much beta amyloid is a bad thing, “every treatment intervention that directly targets beta amyloid has been ineffective or equivocal. So far, there is no absolute evidence in humans that lowering beta amyloid is a good thing from a therapeutic perspective.”

He also cautioned that the 60-mg dose of Celexa used in the study is high compared to the usual doses of 40 mg or 20 mg in older people. And, he added, it’s important to be aware that Celexa has a significant side effect: it can disrupt the heart’s rhythms.

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning that stated Celexa should not be given at doses greater than 40 mg a day since it can cause a dangerous irregular heartbeat at higher doses.

More information

For more about Alzheimer’s disease, visit the U.S. National Institute on Aging.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.