TUESDAY, Jan. 19 (HealthDay News) — A study of obsessive-compulsive Dobermans might someday help explain similar repetitive behaviors in humans.

Scientists have identified a region on chromosome 7 in obsessive-compulsive dogs that may correlate to the human version of the psychiatric disorder.

The gene is the same in humans, said Dr. Nicholas Dodman, first author of the study, which appears as a letter to the editor in the January issue of Nature Molecular Psychiatry. In humans it resides on chromosome 18, the same chromosome which holds all of the psychiatric genes identified thus far, he said.

“It’s certainly true we have basically the same gene in us, so it’s an intriguing lead, but there’s a lot more work that has to be done to see if this particular finding is relevant to human health and obsessive compulsive disorder [OCD],” added Dr. Michael Slifer, an assistant professor of human genetics and genomics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

“But even if this particular finding is not directly relevant, it still gives us clues as to the pathways and processes that may be going on in humans as well as some possible targets for intervention and treatment,” he added.

And, Slifer cautioned, “This gene probably does not have as robust an effect in humans as it does in dogs because we haven’t found it yet in humans [in relation to OCD]. This one would have come out already. But that doesn’t mean it might not still be relevant in a small subset [of people with OCD].”

Some 2 to 3 percent of humans suffer from OCD, marked by repetitive thoughts and behaviors, such as repeated hand-washing.

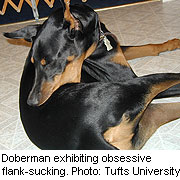

Canine compulsive disorder seems to affect certain breeds, notably bull terriers, which can have a tendency to maniacally chase their tails, and Dobermans, which will compulsively suck on blankets or on themselves.

“These are not just funny things,” said Dodman, professor of clinical sciences at Tuft University’s Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine in North Grafton, Mass. “It’s a physically injurious and life-threatening disease and can seriously impair the relationship between owner and dog, which can lead to euthanasia.”

“There [has been] no explanation for it and it’s clearly genetically driven,” added Dodman, who is also the author of several well-known animal behavior books.

Up to 70 percent of puppies in certain Doberman litters can be afflicted, he said. One German shepherd bit his tail so badly that he bled to death, he added.

“While we have known the flank-sucking in Dobermans had to have a genetic component because it occurred in certain bloodlines, this study confirms it and identifies where the trait is carried,” said Bonnie Beaver, professor in the department of small animal clinical sciences at the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences of Texas A&M University in College Station. “It provides a starting place to look at genetic relationships of other compulsive disorders and . . . might help the understanding of compulsive human disorders and be able to differentiate the genetic ones from the environmental ones.”

Chromosome 7 appears within the cadherin-2 gene (CDH2), which is involved in communication among neurons in the brain.

And cadherins, proteins that enable cells to adhere or stick to each other, are also involved in human obsessive-compulsive disorders. Recently, cadherins were linked to autism spectrum disorder, also characterized by compulsive behaviors, such as repetitive head-banging.

The Tufts researchers teamed up with the Program in Medical Genetics at the University of Massachusetts and the Broad Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to test Doberman blood samples that the Tufts staff had collected and stored for more than a decade.

Dobermans who (in this case) compulsively sucked on their flanks or on blankets, were more likely to have this gene sequence than healthy dobermans.

Beaver said the findings were “exciting” and that “the number of dogs used in the study places good confidence levels on the findings.”

More information

There’s more on obsessive-compulsive disorder at theU.S. National Institute of Mental Health.