FRIDAY, May 17 (HealthDay News) — There are apps that turn your smartphone into a metal detector, a musical instrument and a GPS system, and now there’s an app that may help doctors save your life if you’re having a heart attack.

The app, which was designed by engineers and critical care physicians, helps doctors rapidly diagnose certain kinds of severe heart attacks, called STEMIs, before patients get to the hospital.

The app currently is in the experimental stage, but it has undergone field testing.

In a STEMI heart attack, which stands for ST segment elevated myocardial infarction, a clot completely blocks blood flow to the heart. About a quarter of a million people have STEMIs each year in the United States.

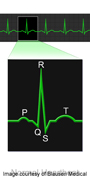

These kinds of heart attacks create a unique pattern of pulses when doctors hook up patients to an electrocardiogram, or EKG, machine, which measures the heart’s electrical activity.

The problem is that doctors need to see the EKG reading, which is called a tracing, to properly diagnose the attack and quickly assemble the team of specialists that is needed to clear the clot.

There are proprietary systems that use EKG machines hooked up to modems to send images back to hospital computers, but those systems are expensive and not all hospitals and EMS systems can afford them.

As an alternative, paramedics can use their smartphones in the field to snap a picture of the tracing and send it to a doctor at the hospital via email.

But as anyone who has ever tried to email a picture from their phone knows, it’s far from foolproof. Large, high-quality images — the kind doctors need to see — can take several minutes to send and receive.

To address the issue, Dr. David Burt, an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Virginia, challenged a class of systems engineering students to develop an app that could shrink images to make them faster to send, but still maintain the clarity needed for diagnoses.

“It’s very easy to use,” Burt said. “You hold it over the EKG tracing, you snap a picture.” Hitting a button sends the image. When it’s finished, the app shakes and makes noise to alert senders to the successful transmission.

“It’s very simple but we want it to be very rugged, so that it’s kind of like a hammer — it always works,” he said. He also wants to offer the app at no cost to doctors and hospitals.

So far, Burt said, they have tested the app more than 1,500 times using different wireless carriers in a city.

They also have pitted the app against the alternative method of using an iPhone to email a picture. In that study, the app consistently sent images within four to six seconds. Emailed images could take nearly two minutes to go through. The app failed less than 1 percent of the time, while the emailed images flopped between 3 percent and 71 percent of the time, according to the study.

The study is scheduled for presentation Friday at an American Heart Association meeting in Baltimore. Studies presented at medical conferences are considered preliminary because they haven’t yet undergone the scrutiny required for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Dr. Iltifat Husain, founder of the iMedicalApps website, which keeps up with news about technology in medicine, said he was impressed by the app, but also by how thoroughly the team has been testing it. Husain estimates that less than 1 percent of apps that are developed for doctors are field tested to see if they actually work.

“Something like this would have to be tested before it was put to use because of how critical the information is that you’re relaying,” said Husain, who was not involved in the research.

Husain, who also is an emergency medicine resident at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., said the time the app shaves off image transmission could be critical.

“The longer you wait, the more heart muscle dies, so every minute counts,” he said. “Actually, every second counts.”

Surviving a STEMI depends on how quickly doctors can restore blood flow, which often is done by snaking a catheter up to the heart and using a small balloon to clear the clot.

“We’ll get an EKG reading and the ER physician will activate the cath lab. Once you activate it, a huge team has to be assembled,” Husain said. “If it’s overnight, people are sometimes coming in from home. If you can get someone coming in from home five minutes faster, I think it’s a big deal.”

More information

For more about heart attacks, head to the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.