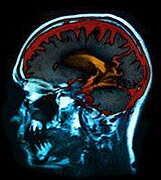

MONDAY, Nov. 28 (HealthDay News) — The brains of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) show abnormalities in certain areas involved with “visual attention,” new research finds.

Researchers performed functional MRIs (fMRIs) on 19 children aged 9 to 15 diagnosed with ADHD and 19 without the disorder while the children took a test in which they were shown a set of numbers and then asked to remember whether a subsequent group of numbers matched the original.

The test requires children to pay attention and stay focused in order to remember the original set, said lead study author Xiaobo Li, an assistant professor of radiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

An fMRI is a specialized type of MRI used to measure brain activity.

The scans showed that the kids with ADHD had less activity in the frontal lobe, parietal lobe and temporal lobe, which is “consistent with previous studies that showed reduced activations in those same regions,” Li said. Those brain regions have also been associated with attention and working memory, she added.

Children with ADHD also showed differences in brain connectivity between regions, including “short-range,” “long-range” and “across-hemisphere” abnormalities, she said.

“What this tells us is that children with ADHD are using partially different functional brain pathways to process this information, which may be caused by impaired white matter pathways involved in visual attention information processing,” said Li, who plans to study the ability of children with ADHD to stay focused on auditory information, or what they hear, next.

The research is slated for presentation Monday at the Radiological Society of North America meeting in Chicago. The data and conclusions of research presented at medical meetings should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

ADHD affects an estimated 5 percent to 8 percent of school-aged children. Symptoms, which can persist into adulthood, include inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity beyond what’s normally seen given a child’s age and development.

Though researchers suggested that the brain connectivity abnormalities could eventually be used as a diagnostic tool for ADHD, other experts say far more needs to be learned first. That would include doing studies with more children, and determining whether the differences in connectivity observed on the fMRI scans are exclusively seen in kids with ADHD or also in children with other conditions.

“To suggest that fMRI should be recommended as an initial evaluation of ADHD patients is certainly not justified at this point and there are no immediate clinical recommendations that would come out of this,” said Dr. Andrew Adesman, chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y.

Though the findings are “far from being a diagnostic tool, it does suggest some brain mechanism is associated with the symptoms,” he added.

There is no single test for ADHD. Currently, doctors diagnose ADHD using information about a child’s behavior from parents and other caregivers and a medical exam to rule out other conditions.

“Diagnosing ADHD is very difficult because of its wide variety of behavioral symptoms,” Li said. “Establishing a reliable imaging biomarker of ADHD would be a major contribution to the field.”

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health has more on ADHD.