WEDNESDAY, Aug. 22 (HealthDay News) — Self-awareness is the product of pathways that are spread throughout the brain, according to a new study.

Researchers say their findings challenge previous theories that people’s awareness of their own feelings and behaviors was confined to just three specific areas of the brain.

“What this research clearly shows is that self-awareness corresponds to a brain process that cannot be localized to a single region of the brain,” study co-author, David Rudrauf, a former assistant professor of neurology at the University of Iowa, said in a university news release. “In all likelihood, self-awareness emerges from much more distributed interactions among networks of brain regions.”

Rudrauf is now a research scientist at the INSERM Laboratory of Functional Imaging, in Paris.

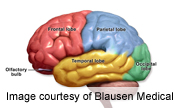

For the study, researchers examined a 57-year old, college-educated man with extensive brain damage to the insular cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex — the three areas previously thought to correspond to self-awareness.

Known as “Patient R,” the man passed all standard tests for self-awareness. He could also identify himself in the mirror or in photos taken at different times in his life.

Following an in-depth interview, the researchers found that Patient R had depth and insight into himself, enabling him to examine his own thoughts and feelings.

“During the interview, I asked him how he would describe himself to somebody,” study first author Carissa Philippi, who earned her doctorate in neuroscience at the University of Iowa, said in the news release. “He said, ‘I am just a normal person with a bad memory.'”

Philippi is now a postdoctoral research scholar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Patient R was able to perceive that actions were the result of his own intentions. Aside from damage to the part of his brain that updates new memories, which caused amnesia, the researchers found all other aspects of the patient’s self-awareness were unharmed.

“Most people who meet R for the first time have no idea that anything is wrong with him. They see a normal-looking middle-aged man who walks, talks, listens and acts no differently than the average person,” Rudrauf said. “According to previous research, this man should be a zombie. But as we have shown, he is certainly not one. Once you’ve had the chance to meet him, you immediately recognize that he is self-aware.”

Patient R had only 10 percent of tissue remaining in his insula and just 1 percent of tissue remaining in his anterior cingulate cortex. Tests on these regions of his brain showed that the remaining tissue was very abnormal and largely disconnected from the rest of his brain. The researchers concluded the brainstem, thalamus and posteromedial cortices all play roles in human self-awareness.

“Here, we have a patient who is missing all the areas in the brain that are typically thought to be needed for self-awareness, yet he remains self-aware,” added study co-corresponding author Justin Feinstein, who earned his doctorate at the University of Iowa. “Clearly, neuroscience is only beginning to understand how the human brain can generate a phenomenon as complex as self-awareness.”

The study was published online Aug. 22 in the journal PLoS ONE.

More information

Visit the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to learn more about the brain and how it works.