THURSDAY, Dec. 2 (HealthDay News) — A type of brain imaging that measures the circuitry of brain connections may someday be used to diagnose autism, new research suggests.

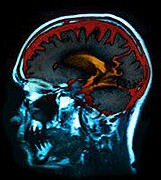

Researchers at McLean Hospital in Boston and the University of Utah used MRIs to analyze the microscopic fiber structures that make up the brain circuitry in 30 males aged 8 to 26 with high-functioning autism and 30 males without autism.

Males with autism showed differences in the white matter circuitry in two regions of the brain’s temporal lobe: the superior temporal gyrus and the temporal stem. Those areas are involved with language, emotion and social skills, according to the researchers.

Based on the deviations in brain circuitry, researchers could distinguish with 94 percent accuracy those who had autism and those who didn’t.

Currently, there is no biological test for autism. Instead, diagnosis is done through a lengthy examination involving questions about the child’s behavior, language and social functioning.

The MRI test could change that, though the study authors cautioned that the results are preliminary and need to be confirmed with larger numbers of patients.

“Our study pinpoints disruptions in the circuitry in a brain region that has been known for a long time to be responsible for language, social and emotional functioning, which are the major deficits in autism,” said lead author Nicholas Lange, director of the Neurostatistics Laboratory at McLean Hospital and an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “If we can get to the physical basis of the potential sources of those deficits, we can better understand how exactly it’s happening and what we can do to develop more effective treatments.”

The study is published in the Dec. 2 online edition of Autism Research.

Dr. Stewart Mostofsky, medical director at the Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Center for Autism and Related Disorders, called the study “intriguing.” However, it remains to be seen if the test is sensitive enough to distinguish between autism and other developmental conditions that impact the brain.

“This is a very preliminary step and one that will require larger samples of children and a broader range of children with autism and other development disorders, particularly other developmental language disorders,” Mostofsky said.

Also unknown is how old a child has to be for the deviations in brain circuitry to show up on the MRI. At birth, the brain’s gray and white matter is largely undifferentiated, although this changes rapidly during the first 18 to 24 months, Lange said.

The specific type of MRI used is called diffusion tensor imaging, which offers information about the structure of the brain as opposed to how the brain “lights up” during particular activities.

Among the specific findings in participants with autism, the fibers in the right side of the superior temporal gyrus were more organized than the fibers on the left; the opposite was true in typical people.

“The left is language. Typical brains have nice, coherent, organized fiber structures,” Lange said. “In those with autism, the left is less organized.”

Researchers repeated the MRI test with a second set of participants and had similar success in predicting who had autism and who didn’t.

More information

The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has more on autism.