MONDAY, Nov. 22 (HealthDay News) — Adding face shields to soldiers’ helmets could diminish brain damage resulting from explosions, which account for more than half of all combat-related injuries sustained by U.S. troops, a new study suggests.

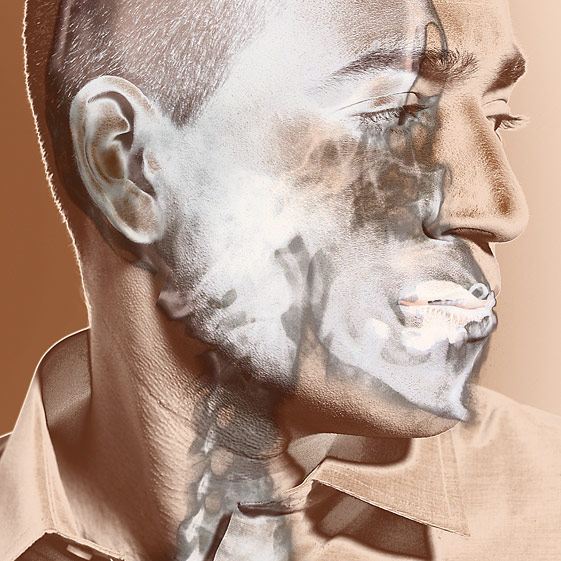

Using computer models to simulate battlefield blasts and their effects on brain tissue, researchers learned that the face is the main pathway through which an explosion’s pressure waves reach the brain.

According to the U.S. Department of Defense, about 130,000 U.S. service members deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq have sustained blast-induced traumatic brain injury (TBI) from explosions.

The addition of a face shield made with transparent armor material to the advanced combat helmets (ACH) worn by most troops significantly impeded direct blast waves to the face, mitigating brain injury, said lead researcher Raul Radovitzky, an associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

“We tried to assess the physics of the problem, but also the biological and clinical responses, and tie it all together,” said Radovitzky, who is also associate director of MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies. “The key thing from our point of view is that we saw the problem in the news and thought maybe we could make a contribution.”

Researching the issue, Radovitzky created computer models by collaborating with David Moore, a neurologist at the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Moore used MRI scans to simulate features of the brain, and the two scientists compared how the brain would respond to a frontal blast wave in three scenarios: a head with no helmet, a head wearing the ACH, and a head wearing the ACH plus a face shield.

The sophisticated computer models were able to integrate the force of blast waves with skull features such as the sinuses, cerebrospinal fluid, and the layers of gray and white matter in the brain.

Results revealed that without the face shield, the ACH slightly delayed the blast wave’s arrival but did not significantly lessen its effect on brain tissue. Adding a face shield, however, considerably reduced forces on the brain.

The study, published online Nov. 22 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, contradicts previous research that suggested that the ACH could mitigate brain injury in service members — the most common injury sustained by soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“This study really has two key contributions,” Radovitzky said. “First, that the ACH doesn’t help a lot for blast protection, and second, but it doesn’t make it worse. We are not saying anything negative about the ACH, just the opposite. With the helmet, we saw a lot of improvement compared to an unprotected face.”

Dr. Michael Lipton, associate director of the Gruss Magnetic Resonance Research Center at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, said one of his concerns about the study is that the only thing modeled was the effect of a blast.

“Really, there’s no such thing as an isolated blast,” Lipton said, explaining that the impact typically knocks one to the ground or causes the head to hit other objects. “There are blast waves, but an impact component also. Very commonly, there’s a whole spectrum of injury. It all depends on the position and proximity of the patient to the blast.”

Lipton pointed out that a face shield wouldn’t just help soldiers involved in heavy explosions, but also in smaller blasts that happen on an everyday basis.

“It’s not uncommon for these soldiers to get exposed to multiple blast injuries without being removed from repeated [combat] exposure recognized as significant injuries,” Lipton said. “Protection might even be more efficacious in repeated impacts.”

Radovitzky said many details need to be addressed before a face shield could be integrated into soldiers’ helmets. Further research will focus on expanding what’s understood about head injuries from blasts, he said.

“There are a lot of things I don’t understand from an operational standpoint of a soldier,” he said. “There’s a lot more we need to know. We are all trying to fill in the gaps and connect the dots.”

More information

Find out more about traumatic brain injuries at the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center.