THURSDAY, March 4 (HealthDay News) — Researchers have succeeded in sequencing 3.3 million genes from organisms residing in the human gut.

And it appears that each person harbors at least 160 species of bacteria in their gut, far more than originally estimated, according to a paper appearing in the March 4 issue of Nature. The research was led by researchers in China as part of the MetaHIT (Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract) project.

Although this is just the first tiny dent in a mountain of work to be done, the findings should help experts understand both human health and human illness better.

“This is so rich. It could help in so many different ways. It could help us understand diseases like inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis. It could help us with problems like malnutrition and obesity. It could help us understand many different metabolic problems from liver disease to kidney to heart disease,” said Dr. Martin Blaser, chairman of the department of medicine at New York University Langone Medical Center and a professor of microbiology at New York University School of Medicine in New York City. “This is really a landmark study.”

Humans coexist peacefully and sometimes not so peacefully with legions of microorganisms in their gut. An estimated 100 trillion cells make up these microbes. That’s 10 times the number of human cells in the body.

“There are symbiotic relationships with these bacteria,” explained Dr. Brian Currie, vice president and medical director for research at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City. “They make substances we need … and there’s a body of literature that suggests that the interaction with these bacteria may have something to do with immune modulation as well. It’s a largely unexplored area.”

Another expert, Jeffrey Cirillo, a professor of microbial and molecular pathogenesis at the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine in College Station, said that, “basically the gut functions properly because of the large amount of bacteria that are present within it.”

“In other words, rather than the gut being controlled by us, it’s actually controlled by the bacteria present in it,” he said. “There’s almost a limitless number of diseases and health characteristics that are affected by what we eat and how it gets digested, and the microflora that are present basically determine how that gets handled. It’s a critical component of health overall.”

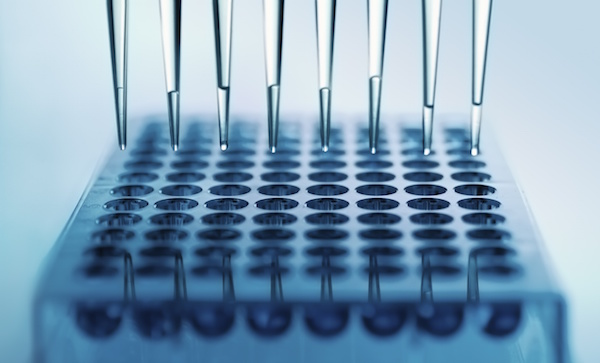

This research team was able to identify and sequence 3.3 million microbe genes from fecal samples taken from 124 Europeans. This is 150 times more microbial genes than human genes.

The participants, from Spain and Denmark, were either healthy or had inflammatory bowel disease.

More than 99 percent of the genes were bacterial, representing up to 1,150 different bacterial species.

Although most of the 3.3 million genes must be shared among individuals, the study authors were only able to show that 38 percent of the genes seen in each individual were shared with at least half of the other individuals sampled.

And while much has been made of “good” bacteria vs. “bad” bacteria in people’s bodies, the organisms involved may not be either.

“This may have to do more with proportions. Maybe there is a certain ecological balance of certain kinds of organisms, and disease is not necessarily due to having bad bacteria but an imbalance,” Blaser said. “When you take a census and you have schoolteachers, policemen, insurance brokers, etc. That’s kind of healthy. But let’s say you took a census and everybody was a Wall Street stockbroker. That may be less healthy. The proportions of the different kinds of organisms that are present could be more important.”

For instance, patients with inflammatory bowel disease had, on average, 25 percent fewer genes than healthy individuals, indicating that patients suffering from IBD have less diversity in their guts.

“We know that some of these functions are critical for human health and well-being, and these are the first initial baby steps to fully characterize what those are, to get a handle on the diversity,” added Dale Hedges, an assistant professor at the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics and assistant director of the Center for Genome Technology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “As we start to get a better grasp of the genetic diversity in our gut biome, we can start to ask questions about the relationship between the genetic diversity that’s existing in our microbiome internally and our susceptibility to different diseases and what the interaction is.”

Cirillo is enthusiastic. “A picture is worth a thousand words, and this gives us a picture of what’s going on in the gut,” he said.

More information

Visit the International Human Microbiome Consortium for more on this type of research.