SUNDAY, July 18 (HealthDay News) — Wouldn’t it be nice if you could get the flu vaccine through a stick-on skin patch instead of a shot?

Experiments in mice show that using skin patches containing tiny, painless “microneedles” to deliver the influenza vaccine may someday be a viable alternative to traditional shots.

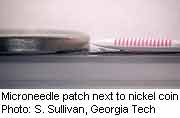

The microneedles — less than 1 millimeter in length, or about half the thickness of a nickel turned on its side — dissolve into the skin and are small enough that they don’t draw blood or cause pain, researchers said.

Better yet, if the patches are found to work in humans, getting an immunization may be as simple as stopping by the pharmacy, picking up your patch and slapping it on.

“For vaccination, it could be a game changer,” said lead study author Sean Sullivan, who did the research when he was a doctoral student at Emory University and Georgia Institute of Technology. “There are so many little annoyances with the [standard] vaccination process that could go away.”

The study is published in the July 18 online issue of Nature Medicine.

Experts agreed the findings were promising. “This is a tremendous advancement in the technology,” said Rick Bright, scientific director of the Influenza Vaccine Project at PATH in Washington, D.C.

Because the patch appeared to work using less vaccine than in a typical shot, the discovery has the potential to reduce the amount of vaccine that needs to be produced, which could alleviate shortages in case of pandemic flu, Bright added.

Dr. Paul A. Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center and chief of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, also called the technology a “breakthrough.”

However, “the caveat is, this needs to be extended to humans,” Offit said. “It’s not uncommon for vaccines or vaccine delivery systems to look very promising in experimental animals, then fail in humans. But there is every reason to believe this kind of technology could be applicable to children and adults.”

Other through-the-skin vaccine delivery attempts have failed to produce enough an immune response, in part because the thickness and water content of people’s skin varies by age, race and ethnicity far more than a mouse skin. However, the new technology appears to overcome that by delivering the vaccine slightly deeper, Bright added.

The next step is getting funding to begin clinical trials, which researchers said they hope to being in the next couple of years.

In a normal flu shot, vaccine is delivered into the muscle. With the patch, the vaccine is encased in water-soluble polymer needles on the patch. When placed on the skin, the needles dissolve almost immediately, delivering vaccine into the skin and provoking a localize immune response.

From there, the immune cells travel via the lymph system through the body, prompting a systemic, or whole body, immunization — at least in mice.

The mice who had the patches showed a robust immune response to the vaccine. In addition, the vaccinated mice easily survived what would have otherwise been a lethal dose of the flu.

In addition to its other benefits, a skin patch vaccine would not have to be refrigerated, a problem in developing countries, and there would be fewer medical waste issues, such as disposing of used syringes, researchers said.

More information

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has more on the flu.