WEDNESDAY, March 31 (HealthDay News) — A new Japanese study outlines the molecular and cellular reasons why some flu vaccines work better than others and could point the way to better protection with fewer side effects.

“By understanding the molecular mechanism of different flu vaccines through our findings, not only the rationale for current live-attenuated influenza vaccine for children, currently available in the United States, is warranted, but also what kind of adjuvant is needed for safer as well as efficient flu vaccine development,” said Dr. Ken J. Ishii, an adjunct professor in the Osaka University Laboratory of Vaccine Science in Suita. He is lead author of a report in the March 31 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

An adjuvant is something added to a vaccine to increase the immune system’s response. Adjuvants are not used in U.S. flu vaccines, although they are added to such vaccines in some other countries.

The journal report describes how Ishii and his colleagues methodically injected mice with the different kinds of flu vaccines that can be used: live virus, which contains a weakened form of the flu virus; inactivated whole-virus, in which the virus has been killed by heat or chemical treatment; and split-virus, which contain a fragment of the virus. The researchers then studied in detail the immune system response to each vaccine.

Split-virus flu vaccines are used in the United States. The study found that whole-virus vaccines provoke a greater immune response, which has both a good and a bad side, said David Topham, a flu virus expert who is an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Rochester in New York.

“The whole-virus vaccine is reactogenic,” meaning that it can cause pain at the site of injection and other side effects, Topham said. The slightly lower immune response produced by a split-virus vaccine is offset by a reduction in side effects, he explained.

The most significant finding of the Japanese study was identification of a rare immune system cell type, dendritic, or plasmacytoid, plasma cells, which control the effect of inactivated flu virus vaccines, Ishii said. The study showed that those cells play no role in the response to split-virus vaccines, “thereby enabling us to understand why and how different flu vaccines work or sometimes do not work well,” he said.

“We know that these dendritic cells are extremely sensitive to viral RNA,” Topham said. “They have different ways of recognizing viruses.”

RNA is the genetic material of influenza viruses.

While the Japanese work “doesn’t contain a whole lot of things we didn’t know before,” Topham said, it does present a valuable map of the flu vaccine territory.

“Our findings certainly help clinicians understand why one shot of the swine flu vaccine worked well and why seasonal vaccines do not work well in children,” Ishii said.

More information

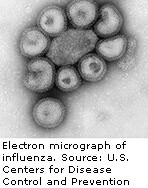

Flu viruses and vaccines against them are described by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.