WEDNESDAY, April 13 (HealthDay News) — Two new studies highlight the complexities hospitals face in controlling and containing the spread of potentially lethal bacteria that are resistant to many antibiotics.

While one study showed that certain interventions could decrease transmissions and infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), the other found no improvement when a somewhat different set of precautions were used. The second study looked at both MRSA and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE).

Overall, though, the news can still be viewed in a positive light, said one expert.

“These organisms are very difficult to manage, but what we have seen over the last several years is that many of these infections are preventable by a variety of measures,” said Dr. Marcus Zervos, director of infection control at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Zervos was not involved in the studies, which appear in the April 14 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

MRSA, which is resistant to all first-line antibiotics, has become a scourge of hospitals. According to an accompanying editorial, MRSA affects more than a quarter of a million hospitalizations each year and contributes to many thousands of deaths annually.

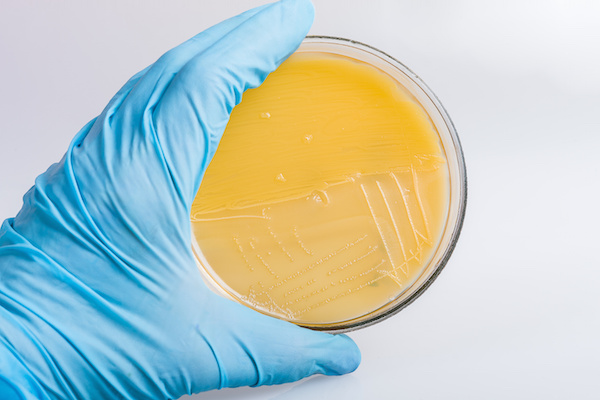

The first study, conducted at different Veterans Affairs Hospitals around the United States, looked at the effect of screening incoming patients for MRSA as well as “contact precautions” such as donning clean gloves and gowns along with using better hand hygiene and educating all staff to consider themselves responsible for infection.

Between October 2007 and June 2010, implementation of this “MRSA bundle” reduced the rate of infections with MRSA and VRE in intensive care units (ICUs) from 1.64 per 1,000 patient days to 0.62 per 1,000 patient days, a 62 percent decline.

In other parts of the hospitals, infection rates dropped from 0.47 per 1,000 patient days to 0.26 per 1,000 patient days, a 45 percent decrease. Infection with Clostridium difficile may also have been reduced, and antibiotic prescriptions did decline.

The second study looked at whether screening patients at admission and use of “barrier precautions” (wearing clean gloves and gowns) when seeing a MRSA or VRE carrier would have an effect on spread within intensive care units. The researchers did not look specifically at infection.

Although many patients carrying MRSA or VRE were identified, the intervention did not have an effect on spread of the bacteria.

“The strategy that we tested as applied in our study would not indicate that this approach is going to be broadly effective, that this would not a one-size-fits-all strategy,” said study author Dr. W. Charles Huskins, a consultant in pediatric infectious diseases at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

This may have had to do with the fact that the health-care providers involved did not use barrier precautions as required, the study noted.

There was also a five-day lag between the time a person was checked for the organism and the time the lab tests came back. “In an ICU, anything can happen in terms of transmission of bacteria,” Zervos said.

Any number of factors could have contributed to the different findings, including different study designs, Zervos said.

But while other precautions are important, Zervos also said that there is still one tried-and-true method for minimizing spread and infection which is perhaps most important and most underused. That method is simple hand washing.

“Hand washing has been shown to be the most important measure to reduce hospital-related infections . . . but studies have shown that hospitals are only 40-to-60 percent compliant,” he said. “That’s something we should just not accept. They should be at 100 percent compliance. There’s no excuse for people not washing hands or using hand hygiene going in and out of patient rooms.”

More information

The Alliance for the Prudent Use of Antibiotics has more on resistant bacteria.