MONDAY, Sept. 16 (HealthDay News) — Potentially fatal invasive infections from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are declining in the United States, according to a new government report.

In a separate study, other researchers have found that high exposure to swine manure spread in crop fields, along with living near swine livestock operations, appears to be linked with MRSA community-acquired infections, a type that continues to puzzle the experts.

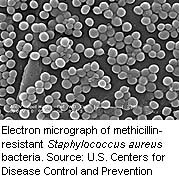

MRSA is considered a “superbug” because of the bacteria’s ability to fight off treatment, including the antibiotic methicillin. It can wreak havoc in health-care settings such as hospitals and nursing homes, especially among elderly and immune-compromised patients, but it also can occur in the community at large.

Both new studies were published online Sept. 16 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Overall, it’s good news,” said Dr. Raymund Dantes, who conducted the first study while an epidemiologist at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The most severe kinds of MRSA infections are declining in the U.S.”

In 2011, over 30,000 fewer invasive MRSA infections occurred than in 2005, Dantes said. Total infections in 2011 were estimated at about 80,400.

Invasive MRSA infections with onset at the hospital dropped the most, with a 54 percent decline, Dantes said. The smallest decline was in community-associated infections, dropping just 5 percent.

Another type — health-care associated community-onset infection — dropped about 28 percent. This describes MRSA in people who’ve had a lot of exposure to health-care settings but are believed to have contracted the infection in the community, said Dantes, who is now an assistant professor of medicine at Emory University.

The researchers collected information from selected counties in nine U.S. states, then took other information into account to estimate the national incidence rates.

“The focus of our study was to quantify the most severe MRSA infections out there,” Dantes said. The researchers did not track noninvasive MRSA infection, the kind that affects skin and soft tissue, but only invasive, “the kind of infection that would kill people.” These MRSA infections can affect the bloodstream, bones, or other areas.

While Dantes can’t say for sure what is behind the decline, he suspects better infection-control practices have helped, such as isolating patients who have MRSA in a hospital or other health-care facilities, as well as better barrier precautions such as doctors wearing sterile gowns.

“The next step in trying to reduce invasive MRSA infections is actually looking at folks outside the health-care setting,” Dantes said.

The second study, on swine-related infection, may provide some clues. Researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health evaluated more than 5,700 patients with MRSA or skin and soft tissue infections, comparing them to nearly 3,000 healthy patients.

The investigators zeroed in on 200 samples taken from those with and without infection, then used Google Earth to find the home addresses of those with MRSA and those without. About 11 percent of the infections may be related to the exposure to livestock operations, they found.

Many antibiotics used in the United States are used for growth enhancement of livestock, and most of these are excreted in manure, the researchers noted. Many of the antibiotics are from the same drug families used to treat human infections, so extensive use can result in drug-resistant bacteria that can spread to humans, either by animal contact or in the food chain, by eating the meat.

Researchers in the Netherlands already have recognized the potential link with livestock exposure, publishing findings as recently as 2012, said Dr. Edward Septimus, a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M Health Science Center and a member of the antimicrobial resistance committee for the Infectious Diseases Society of America. He reviewed the new studies.

The report of declining infections, he said, is welcome but not surprising news. The new report “confirms the trends we have seen in the last three or four years,” Septimus added.

“The good news is, we are making progress,” he pointed out. “It doesn’t mean Staphylococcus aureus is no longer an important pathogen, because it is.”

He also credits better infection-control practices for the decline, along with more awareness.

To minimize risk of invasive MRSA, Dantes and Septimus suggested following good hygiene at home, washing hands regularly and keeping any open area on the skin clean. Loved ones of hospitalized patients should make sure that those who care for the patients follow good hygiene practices, such as washing their hands before exams.

More information

To learn more about MRSA, visit the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.