FRIDAY, Jan. 4 (HealthDay News) — Implantable heart defibrillators aimed at preventing sudden cardiac death are as effective at ensuring patient survival during real-world use as they have proven to be in studies, researchers report.

The new finding goes some way toward addressing concerns that the carefully monitored care offered to patients participating in well-run defibrillator investigations may have oversold their related benefits by failing to account for how they might perform in the real-world.

The study is published in the Jan. 2 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“Many people question how the results of clinical trials apply to patients in routine practice,” lead author Dr. Sana Al-Khatib, an electrophysiologist and member of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C., acknowledged in a journal news release. “[But] we showed that patients in real-world practice who receive a defibrillator, but who are most likely not monitored at the same level provided in clinical trials, have similar survival outcomes compared to patients who received a defibrillator in the clinical trials.”

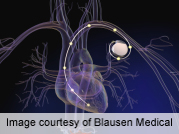

The findings stem from a survival analysis (involving data collected since 2005 by a large national Medicare registry) following implantation with the small electrical devices known as implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) that are connected by wire to the heart and designed to provide a life-saving electronic pulse if and when the heart stops beating.

The research team compared the performance of such devices among more than 5,300 real-world patients with the performance observed among more than 1,500 patients who had participated in clinical defibrillator studies. The authors stressed that the demographics of the two groups were comparable, with no particularly sick or elderly individuals included in the real-world pool.

But while the analysis revealed comparable results among both groups, the authors stressed that their findings clearly could not speak to how older and sicker patients might fare outside the confines of a study situation, which itself often favors the inclusion of younger/healthier patients.

“That is an issue, and the only way to get at that is to randomly assign such patients to either receive an ICD or not in a clinical trial,” Al-Khatib said in the news release. “Even without those data, however, our study gives patients and their health care providers reassurance that what we have been doing in clinical practice has been helpful, and is improving patient outcomes. Our findings support the continued use of this life-saving therapy in clinical practice,” she added.

More information

For more on ICDs, visit the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.