TUESDAY, Jan. 29 (HealthDay News) — Most heart patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) would prefer to switch off the device if they had an advanced illness, new research suggests.

“We found that the majority, 71 percent, would opt to have their ICD deactivated if they had the choice,” said study co-author Dr. John Dodson, a cardiologist and postdoctoral research fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He conducted the research while completing his fellowship training at Yale School of Medicine.

He and Yale colleagues published their findings in a research letter that appeared online Jan. 28 in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dodson said the findings contrast with earlier surveys of patients with implantable defibrillators that showed most didn’t want their devices deactivated.

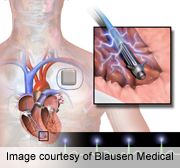

Implantable defibrillators are prescribed for patients who are at risk for life-threatening, abnormal heart rhythms, called arrhythmias. If the ICD senses one of these arrhythmias, it sends a high-voltage shock to restore a normal heart rhythm and protect the patient from cardiac arrest.

The Yale scientists wanted to sort out why previous surveys indicated that patients would prefer to keep the devices turned on, even though other end-of-life defibrillator studies showed the shocks were painful and disturbing.

“The shocks are very painful — like a kick in the chest,” Dodson explained. “They may prolong suffering that won’t improve lives in a measurable manner.”

The researchers recruited 95 heart patients over the age of 50 who had ICDs — 28 percent were women — and surveyed them over the telephone. The researchers began by asking two general questions: “What do you feel are the potential benefits of your ICD?” and “What do you feel are the potential harms of your ICD?”

Next, they read a script to the participants that listed the benefits and burdens of ICDs according to current research. In the final portion of the survey, they asked whether participants would want their ICD deactivated in five different scenarios: if they were permanently unable to get out of bed; if they had permanent memory problems; if they were a burden to family members; if they required prolonged mechanical ventilation; or if they were suffering from an advanced incurable disease.

The survey takers responded using a scale of one (“definitely no”) to five (“definitely yes”). Sixty-seven (71 percent) of the 95 participants wanted ICD deactivation in one or more of the scenarios, the study authors reported in their letter. Sixty-one percent wanted deactivation if they were suffering with an advanced incurable disease, and 24 percent wanted deactivation if they were to become permanently unable to get out of bed.

Dodson said their findings might be different from previous study results for several reasons.

“Generally those studies focused on younger patients with advanced heart failure. Younger patients tend to want more done,” he said. The previous surveys might also “not get at their understanding of what an ICD does,” he added.

“Our survey explained the purpose of their device. A sizable number of participants did not have a good understanding of the benefits or potential burdens of their ICD,” Dodson said.

One heart expert called the new study “eye-opening.”

“It really caught my eye how little some of these patients understand about these devices,” said Dr. Dan Bensimhon, director of the Advanced Heart Failure Program at Cone Health in Greensboro, N.C. “We really have to do a better job making sure people understand what they are getting. That said, our quality of care in heart failure is, in part, measured by what percentage of our patients get these devices.”

It also surprised Bensimhon that only 24 percent would want their device turned off if they were permanently bedridden.

“I think some people just want to hold on to life at all costs,” he said. “I think people equate it with giving up. For somebody who has fought with heart failure for a long time, after all these years, it’s symbolic.”

Dr. James Tulsky, chief of Duke Center for Palliative Care at Duke University, said that while ICDs have “tremendous” value for many patients, when someone reaches the end of life, goals for care may not match with the goal of having an ICD.

“If someone’s dying from heart failure — the inability to pump enough blood — if they’re dying that way, they are going to die anyway and the ICD will basically continue to shock the heart. It’s clearly an undesired outcome and traumatic for the patient and everyone on the scene,” Tulsky said.

Deactivating the defibrillator is a simple matter, said study author Dodson. A wand is held up to the device and programs it off. He said there is no surgery involved and no risk.

The research results carry important messages for patients, physicians and the health care system, he added.

“We need to make sure we’re addressing ICD deactivation with patients, and determining the right time for addressing it. I’m not sure of the answer — in the clinic, or once the patient is in the hospital? And what is the optimal way to counsel people on this? It should be investigated further,” Dodson said.

The challenge, Bensimhon said, is that the current health care climate does not allow enough time for the discussions that ICD patients and doctors need to have about end-of-life care.

“These things are really complicated. To sit down in someone’s room and explain to them takes a long time,” he said. “Today, for example, I saw about 25 patients in clinic. You have 15 minutes with each. To explain to someone why they want their defibrillator turned off, that takes an hour.”

More information

The U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute has more about implantable defibrillators.