THURSDAY, March 7 (HealthDay News) — Heart patients who have an implantable defibrillator known as a CRT-D and who unintentionally lose even a few pounds fare worse than those who do not lose weight, according to a new study.

Although it would seem that people with heart failure who are overweight or obese would do better by losing weight, previous research has found that obese patients with heart failure do better overall than those who aren’t obese, said study author Dr. Valentina Kutyifa, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Rochester Medical Center, in New York.

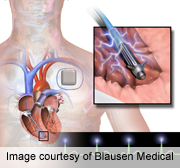

To further understand that paradox, Kutyifa’s team looked at the effects of unintended weight loss in patients with the CRT-D. The implanted device works by sending out small electronic impulses to correct the heart’s rhythm. It also improves the ability of the heart to pump blood, which is a problem in those with congestive heart failure.

When dangerous rhythms are detected, the device shocks the heart back into a normal rhythm. The CRT-D makes up about one-third of all implanted devices such as pacemakers and defibrillators, Kutyifa said.

“The more weight the patients lost, the worse the outcome was,” Kutyifa said. “Over the whole follow-up of 29 months, those who lost 4.4 pounds or more had an 82 percent higher risk of heart failure or death.”

Heart failure was defined as an episode severe enough that the patient had to go to the hospital.

Kutyifa is scheduled to present the findings Saturday at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting in San Francisco. Data and conclusions presented at medical meetings should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

For the study, Kutyifa evaluated nearly 1,000 men and women with congestive heart failure who had a CRT-D implanted, and followed them for 29 months. At the start of the study, most patients were overweight or obese.

One year after the study started, she calculated weight changes; 824 of the patients did not lose weight and, although none of the patients were trying to lose weight, 170 did. About 20 percent had lost more than 4.4 pounds at the one-year mark.

“For each [2.2 pounds] of weight loss, there was a 4 percent increase in heart failure or death,” Kutyifa said.

Whether patients were obese or not to start with, they had a higher risk of heart failure or death if they lost weight, Kutyifa said.

The study found a link between weight loss and increased risk of heart failure and death, not cause-and-effect relationship. It didn’t go into the reasons for the association, but Kutyifa speculates that those who lost weight without trying “may have some kind of worsening in cardiac function or in their general health status, and that is translated into worse clinical outcomes.”

For those with the defibrillator who want to lose weight for health reasons, Kutyifa suggested they do so under the supervision of a doctor. Those who aren’t trying to lose weight but do anyway should tell their doctor so they can be monitored for any problems, she said.

“Weight loss may be a warning sign in these patients,” she said.

A heart expert discussed the study results.

“Dehydration or overtreatment may have played a role in the weight loss,” said Dr. Ravi Dave, a cardiologist at UCLA Medical Center, Santa Monica.

The pounds shed may primarily reflect a loss of water, said Dave, who also is a clinical professor of medicine at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine.

“It will be very important not to send the wrong message,” Dave said. “We do know that to reduce risk for heart disease, weight loss is important.”

The findings need to be looked at in additional studies, he said.

More information

For more information on defibrillators, visit the American Heart Association.