WEDNESDAY, April 3 (HealthDay News) — Advanced prostate cancer patients who are given drugs aimed at lowering their testosterone production to slow the spread of tumors don’t get much benefit if the drugs are given only intermittently.

A large international study suggests that the treatment, called intermittent androgen deprivation therapy, may actually do more harm than good, although the numbers are vague and the regimen may temporarily reduce some side effects.

“It’s not clear whether there is a benefit to intermittent therapy,” said study lead author Dr. Maha Hussain, co-leader of the Prostate Cancer Program at the University of Michigan. However, she added, “in terms of survival, it’s not superior.”

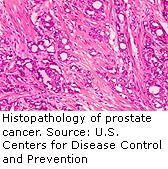

At issue are patients with prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. Their prognosis is typically grim, and as part of their treatment, many receive hormone-therapy drugs aimed at stopping the body’s production of testosterone. The treatment is either continuous or is intermittent to give patients relief from side effects of the therapy.

The treatment, a form of castration via medication, isn’t easy to tolerate. It essentially causes a form of male menopause, Hussain said. “You end up getting symptoms that are quite distressing, such as hot flashes, weight gain, reduced muscle mass and impotence, and libido goes down,” she said.

But it does slow the spread of the disease in about 90 percent of patients, Hussain said, although at some point most patients become immune to the treatment.

In the new study, researchers analyzed the experiences of more than 1,500 men with newly diagnosed, metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, who were assigned to continuous or intermittent treatment with testosterone-lowering drugs and tracked for a median of more than nine years.

Men with a stable or declining PSA level equal to or below a cut-off of 4 ng/ml were randomly assigned to continue or to discontinue the hormone therapy. The therapy was resumed for those in the intermittent group when the PSA climbed to 20 ng/ml.

According to the findings, there was a 10 percent increase in the risk of death with intermittent therapy. Average survival was 5.8 years for the continuous group and 5.1 years for the intermittent group.

But the study called the findings “statistically inconclusive” for figuring out which treatment helps men live longer. And men who took the intermittent treatment did report better quality of life and mental health three months into the study, but not afterward.

Hussain said continuous treatment should remain the standard if the focus is on extending life. But those worried about side effects could still consider the intermittent treatment, she added.

The study, which didn’t examine how much each kind of treatment costs, appears in the April 4 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine.

Dr. Bruce Roth, a professor of medicine in the division of oncology at Washington University in St. Louis, said the standard of care should probably remain the continuous approach. Some doctors are currently experimenting with the intermittent approach, he said, although there has been a shortage of high-quality research to support it.

The good news, he said, is that physicians are moving closer to turning prostate cancer into a chronic yet treatable disease, like high blood pressure and diabetes.

More information

For more on prostate cancer, try the U.S. National Library of Medicine.