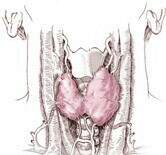

MONDAY, May 17 (HealthDay News) — Immediate treatment of thyroid cancer that has not spread beyond the gland doesn’t make much difference in long-term survival, according to a study that quickly aroused controversy.

“One thing that really surprised me was how good survival was,” said Dr. Louise Davies, lead author of a report on the study, published in the May issue of Archives of Otolaryngology. “We found that for cancers of any size that are confined to the gland, the 20-year survival rate for those that got immediate treatment was 99 percent, and for those not treated immediately, in the first year or even longer after diagnosis, 20-year survival was 97 percent.”

That finding “led me as a surgeon to think about the risks versus the benefits of surgery for such thyroid cancers,” Davies said. “It certainly made me feel a lot less anxious about working with these patients to watch small thyroid modules and not biopsy every one. I’m a lot less worried than I used to be that there will be a cancer in that module that is going to kill a person.”

That conclusion drew a quick rebuttal from Dr. Erich M. Sturgis, an associate professor of head and neck surgery at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and co-author of an accompanying editorial.

“Our concern is that a general person reading that paper will draw the conclusion that there is no size limit to a tumor of that gland that can be observed rather than treated,” Sturgis said.

Davies, an assistant professor of surgery in the Dartmouth Medical School section of otolaryngology and a staff surgeon at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in White River Junction, Vt., was also the author of a 2006 report that started an ongoing controversy about the incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States. That paper reported a sharp increase in the number of thyroid cancers being diagnosed, and oncologists are still divided about whether the increase should be attributed to overdiagnosis or some unknown factor.

About 37,000 new cases of thyroid cancer are diagnosed each year in the United States, and about 1,600 people die from the disease each year, according to National Cancer Institute estimates.

In the new study, Davies and her colleagues used a national data base to compare 35,223 people diagnosed with thyroid cancer who had immediate radiation treatment or surgery with 440 who did not. The 20-year survival rates were determined by projecting the death rates in the two groups over periods of six to eight years.

Davies said the finding has led her to restrict treatment to people where there were signs of danger — difficulty swallowing, changes of voice (the thyroid gland is in the neck), radiation exposure to the head and neck or a family history of the cancer.

“For those patients, the risk of surgery is outweighed by the benefits,” Davies said.

However, Sturgis contends that the conclusion of the new study is flawed because the national data base provides incomplete information. “Sometimes patients may have had unconventional treatment that doesn’t get coded,” he said. “For example, removal of a nodule may get coded as a biopsy.”

Overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer does appear to be a problem, Sturgis said, and many biopsies — tissues samples — are being done when they shouldn’t be. Current guidelines say that nodules less than 1 centimeter in size should be followed by imaging rather than by biopsies, he said.

Age is one factor in deciding whether to treat or observe that is not mentioned in the new study, Sturgis said. “An elderly patient with a small nodule is different from a young patient with a small nodule,” he said.

And though the difference in survival over 20 years is only 2 percent, “treatment is better than observation, although it is a small difference,” Sturgis said.

Dr. J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, described the study as “thought-provoking,” but said the conclusion that so many thyroid cancers can be left untreated is “risky.”

“The numbers are simply too small, and there are so many unanswered questions to justify a physician saying to a patient, ‘It won’t hurt you if we just follow this cancer,’ ” Lichtenfeld said. “That would require a completely different kind of study.”

More information

To learn more about thyroid cancer, visit the U.S. National Cancer Institute.