TUESDAY, June 4 (HealthDay News) — For the extremely obese, the benefits of weight-loss surgery generally outweigh the risks of the procedure. Now, new research suggests that the same might be true for less-obese people as well.

For those who are mildly or moderately obese, weight-loss surgery can improve type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and high cholesterol more effectively than conventional diabetes management and lifestyle changes, new research suggests.

“We’re seeing a pattern in these studies. There’s a definite impact on the diabetes after surgery. Some people don’t respond so well, but most do,” said Dr. Bruce Wolfe, a professor of surgery and co-director of bariatric surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, in Portland.

But, he added, “We need longer-term studies to identify who’s the right candidate for surgery, and we need a number of years of follow-up and a fairly large study population to see if the diabetes improvements after surgery prevent the heart disease, blindness and kidney disease associated with type 2 diabetes.”

Results of the two new studies, as well as an accompanying editorial written by Wolfe and colleagues, are in the June 5 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Body mass index (BMI) is a measurement calculated with height and weight that’s used to estimate the amount of body fat someone has. A BMI of 18 to 24.9 is considered normal weight while 25 to 29.9 is overweight, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mild to moderate obesity is between 30 and 39.9, and 40 and above is morbidly (or extremely) obese.

Normally, weight-loss surgeries are done on people who have a BMI of 40 or above. The surgery is also done on people who have a BMI of 35 or more if they have heart disease risk factors, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol or sleep apnea, according to Wolfe.

The first study was a review of previous research on non-morbidly obese people with type 2 diabetes. The authors searched the medical literature and among other related studies, found three randomized controlled clinical trials that compared weight-loss surgery (also known as bariatric surgery) to nonsurgical treatments, such as diabetes medications and lifestyle changes.

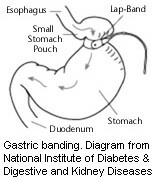

Weight-loss surgeries — including gastric bypass and gastric banding — were associated with a greater weight loss than nonsurgical treatments. Weight-loss surgeries led to as much as 32 to 53 pounds more weight loss and also to greater improvements in blood sugar levels.

“I think we found some promising results for the lower BMI patients with diabetes. There were better results in terms of controlling glucose [blood sugar] and weight loss over one to two years. That we have a way to provide some sort of successful treatment is exciting. But, we don’t yet know how sustainable these changes are. We need longer and larger studies,” said Dr. Melinda Maggard-Gibbons, lead review author, and an associate professor with RAND Health in Santa Monica, Calif.

The second study included 120 people from four teaching hospitals in the United States and Taiwan. They all took part in an intensive lifestyle and medical management program before the study, and half of the group was given gastric bypass surgery.

All had a BMI between 30 and 39.9, with an average of 34.3 in the medical management group and 34.9 in the surgery group. They also all had type 2 diabetes.

A year later, 28 people from the surgery group and 11 people from the medical management group met the study’s goals. These goals were to have an HbA1C level of below 7 percent (a measure that indicates good blood sugar control); LDL or “bad” cholesterol of less than 100 milligrams per deciliter; and systolic blood pressure (the top number) of less than 130.

Overall, those in the surgical group needed three fewer medications. They also lost significantly more of their initial body weight — about 26 percent for the surgical group compared with 8 percent for the medical management group, the study found.

However, there were 22 serious adverse events in the surgical group compared with 15 in the medical management group. And, one person in the surgical group had a number of complications that eventually led to brain damage, which will likely be permanent.

“The risk of these surgeries is fundamentally low, but we can’t make it zero. Most of the complications can be managed. But, disasters can occur, and if you’re that one, any benefit of surgery is lost,” Wolfe said.

Cost is another issue. A weight-loss surgery may cost $20,000 and up, according to the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. And, insurance may or may not pay for the procedure, as there isn’t yet clear evidence of a long-term benefit for people who are less obese.

“There are a whole host of contributing factors to consider. At some point, the surgery will be identified to work best in some and not so well in others. We understand this in cancer treatment, and we want to be able to do the same thing with weight loss surgery, and this is a part of the process to get there,” Wolfe said.

So, what should folks with lower-level obesity and type 2 diabetes do? Wolfe said to start with making a concerted effort to lose weight and exercise regularly, and to make sure you use any diabetes medications prescribed for you exactly as your physician directs you to.

“If this doesn’t work, consider surgery. If you have risk factors, like diabetes, you can appeal a negative insurance decision and ask for an exception,” he suggested.

Maggard-Gibbons also suggested talking to your doctor or a bariatric surgeon about the possibility of enrolling in a clinical trial.

More information

Learn more about weight-loss surgery from the U.S. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.