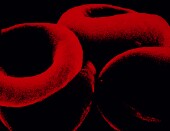

THURSDAY, June 24 (HealthDay News) — In an effort to uncover why some people’s blood platelets clump faster than others, a genetic analysis has turned up a specific grouping of overactive genes that seems to control the process.

On the plus side, platelets are critical for fending off infections and healing wounds. On the down side, they can hasten heart disease, heart attacks and stroke, the study authors noted.

The current finding regarding the genetic roots driving platelet behavior comes from what is believed to be the largest review of the human genetic code to date, according to co-senior study investigator Dr. Lewis Becker, a cardiologist with the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Our results give us a clear set of new molecular targets, the proteins produced from these genes, to develop tests that could help us identify people more at risk for blood clots and for whom certain blood-thinning drugs may work best or not,” Becker said in a Johns Hopkins news release.

“We can even look toward testing new treatments that may speed up how the body fights infection or recovers from wounds,” he added.

The study findings were published online June 7 in Nature Genetics.

The researchers’ efforts focused on blood samples taken from 5,000 American men and women. The samples were ranked according to platelet “stickiness” during clumping, and the scores were matched up against about 2.5 million possible genetic code changes in order to link the speed of platelet clumping with specific gene behavior.

This led the investigators to identify seven genes that appeared to have a big impact on the speed and quantity of platelet clumping. In fact, the grouping was 500 million times more likely than other genes to have an effect on clumping, the researchers noted.

“It was not until now that we put together all the major pieces of the genetic puzzle that will help us understand why some people’s blood is more or less prone to clot than others and how this translates into promoting healing and stalling disease progression,” Becker stated in the news release.

“Our combined study results really do set the path for personalizing a lot of treatments for cardiovascular disease to people based on their genetic makeup, and who is likely to benefit most or not at all from these treatments,” he added.

More information

For more on platelets, visit The Franklin Institute.