TUESDAY, Dec. 8 (HealthDay News) — More than one-fifth of patients on dialysis who undergo angioplasty are given blood thinners they should not be given, new research shows.

As a result, these patients are subject to a higher rate of bleeding during their hospital stay and may even be at a higher risk of dying, according to a report in the Dec. 9 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The drugs in question are enoxaparin (Lovenox), a low-molecular-weight heparin, and eptifibatide (Integrilin). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has determined that neither medication should be used in people undergoing dialysis.

“The study does validate the FDA’s directed labeling [of these drugs] as contraindicated, and it supports avoiding use of these drugs in dialysis patients,” said study author Dr. Thomas Tsai, director of interventional cardiology at the Denver VA Medical Center and an assistant professor of cardiology at the University of Colorado Denver.

“I was surprised by this,” said Dr. Gregory Dehmer, a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine and director of the cardiology division at Scott & White in Temple, Texas. “Clearly this indicates there’s a tremendous opportunity for improvement on the part of interventional cardiologists.”

According to Tsai, this particular type of medicating error may stem from the simple fact that there are so many possible medications for physicians to choose from now.

“Clearly, there’s an explosion of different medications out there,” he said. “I did some calculations, and found 60 combinations of medication alone that we’re faced with using in the cath lab for these patients. If you take into consideration the order in which they’re administered, there are over 1,000 permutations.”

Ease of use and convenience may also play a role in doctors’ turning to these particular drugs, Tsai said.

Meanwhile, the population of people undergoing dialysis is also exploding, and is projected to pass the 2 million mark worldwide by 2010, according to the study.

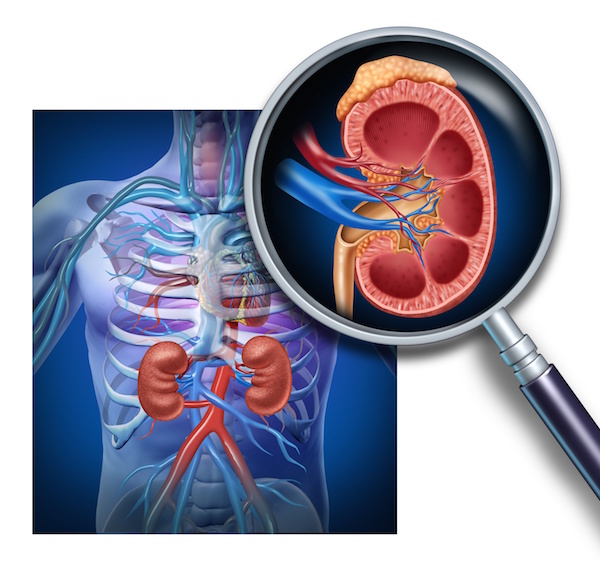

Angioplasty, also known as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), involves widening a blood vessel to ease the flow of blood in patients with narrowed arteries.

For this study, data on 22,778 dialysis patients who had undergone PCI between 2004 and 2008 revealed that 22.3 percent received a blood thinner they should not have been getting. Almost half received enoxaparin and almost two-thirds eptifibatide. About 11 percent received both.

Those patients who did receive a contraindicated drug had a 66 percent higher risk of in-hospital bleeding, and there was some indication that mortality risk might have been elevated as well.

“There was a signal towards increased in-hospital mortality … so there is a possible trend,” Tsai said, adding that this linkage was not yet certain.

Such errors could be introduced at any step in the continuum of care, from the emergency room to the cath lab and anywhere in between, Dehmer said.

“This reflects poorly on the entire process of care, which may start at the outlying hospital or may start in the cath lab,” he said. “This represents a very strong call to action on the part of all those who are involved with the care of patients who ultimately wind up having PCI.”

Health-care providers do have access to alternative blood thinners when treating this group of patients.

And these contraindicated drugs might even work in hemodialysis patients at the right doses, it’s just that no one has ever looked at this, explained Dr. William O’Neill, executive dean for clinical affairs at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

“Poor kidney function almost always disqualifies patients from clinical trials,” he explained. “Do the drugs get filtered out [of the bloodstream by the kidneys]? Basically nobody knows because nobody has done the trials. There is just an absolute glaring lack of information about how to use these drugs in these patients. This study does suggest a fundamental lack of understanding of these drugs among a significant minority of physicians.”

More information

The American Heart Association has more on percutaneous coronary intervention.