TUESDAY, Oct. 9 (HealthDay News) — Children and adolescents with the bleeding disorder hemophilia are at increased risk for bleeds when they participate in some contact sports, but the overall risk is low and varies by sport, a new study shows.

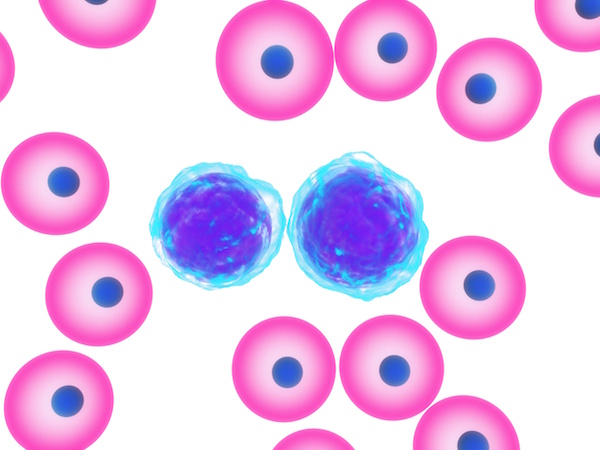

People with hemophilia lack one of the blood proteins necessary for clotting. Because clotting helps stop bleeding, people with hemophilia may bleed longer than people without this disorder. For a long time, they were told that they could not and should not exercise due to risks of bleeding. Times have changed, however, and thanks to better treatments, many are now encouraged to play some sports.

The new study, published in the Oct. 10 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, puts real numbers on risks associated with specific sports for children and adolescents with hemophilia.

Researchers looked at the increased risk for bleeding associated with vigorous physical activity in 104 Australian boys with hemophilia aged 4 through 18. Participants had moderate or severe hemophilia and were monitored for bleeds for up to one year to determine what preceded the event including physical activity and sports participation.

In all, 436 bleeding episodes resulted. Of these, 336 occurred without another bleeding episode in the preceding two weeks. Eighty-eight participants reported at least one bleed. Knees, ankles and elbows were the most frequent sites of bleeding. Most bleeds happened within an hour of the physical activity.

The level of risk varied by sport. Specifically, compared with being inactive, the risk of bleeding is nearly three times greater when playing limited-contact sports such as soccer and basketball, and four times greater when playing contact and collision sports such as rugby and wrestling, the study showed. Put another way: For a child who bleeds five times a year and plays basketball twice weekly and wrestles once a week, the sports are only linked to one of the five annual bleeds, the study authors explained.

“Sport and physical activity is beneficial for children with hemophilia, but the benefits must be balanced against the increased risk of bleeding episodes, particularly bleeding into muscles and joints,” said study author Dr. Carolyn Broderick of the University of New South Wales in Sydney. If untreated, hemophilia causes recurrent bleeding into joints.

“Children will be at increased risk of bleeding while playing sports, but because the increased risk is only present while the activity is being performed and involvement in vigorous physical activity only involves a small number of hours in the week compared to the number of hours spent inactive, the absolute increase in number of bleeding episodes associated with sport may be small,” Broderick explained. “This is likely to be reassuring for parents.”

Non-contact physical activities are most appropriate for children with hemophilia, but sports with limited contact may also be OK. “Collision sports are best avoided but, in countries where prophylactic [preventive] clotting factor is available, administration of clotting factor immediately preceding contact and collision sports significantly reduces bleeding risk,” Broderick said.

“Of course, sports in which there is a high risk of direct trauma to the head or vital organs, for example boxing, should be avoided as the consequences of a bleed into the brain or other vital organs could be catastrophic,” Broderick stressed.

Preventive treatments with clotting protein and conditioning measures can really level the playing field for children with hemophilia who want to play sports, said Dr. Marilyn Manco-Johnson, a pediatric hematologist at the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado, in Aurora.

“We have come so far in developing good, safe and effective products so we can take away most of the risks for these children,” said Manco-Johnson, who wrote an editorial accompanying the new study. “We can replace blood proteins to diminish the risk of bleeding with injury, and the second risk is getting an injury that might need surgery or cause muscle or joint damage down the road.”

Proper training can help reduce these risks, according to Manco-Johnson. “Children with hemophilia need to work a little harder to build muscles and strength,” she added. People with hemophilia don’t heal as well after surgery to repair damaged muscles or joints as their peers without the bleeding disorder.

Exercise is good for these children, another expert said.

“The bottom line is moderate exercise is very important and helps kids with hemophilia develop stronger muscles and joints and is highly recommended, but vigorous activity is the question mark,” said Dr. Ziad Khatib, a pediatric hematologist at Miami Children’s Hospital. “If somebody loves a sport, I do not recommend that they abandon it because with appropriate prevention, they can do well.”

Limits do exist, Khatib noted. “Children with severe hemophilia will never be on a professional or college level football or basketball team,” he said. “Most will be happy with mild to moderate exercise for fun.”

More information

Learn more about hemophilia at the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.