WEDNESDAY, Oct. 20 (HealthDay News) — If you’re taking the blood-thinning medication warfarin, a new study suggests that you might not always need to visit the doctor to get your medication levels checked.

The study, which is published in the Oct. 21 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, found that weekly home tests were similarly effective to monthly clinic testing for patients taking warfarin therapy.

The study compared clinic-based testing to home testing for about 3,000 patients taking the anticoagulant drug, explained one of the study’s authors, Dr. Rowena Dolor, an assistant professor in the division of internal medicine at Duke University Medical Center, and a staff physician at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Durham, N.C. “While the study showed no difference in long-term outcomes, those on home testing spent more time in the target range for medication levels,” she said.

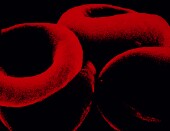

Blood-thinning drugs such as warfarin, also known as anticoagulation therapy, are prescribed to help keep the blood from clotting excessively, as this can cause ischemic strokes or heart attacks. However, too much of these medications can also cause problems, such as serious internal bleeding or a hemorrhagic (bleeding) stroke.

The reason it’s so hard to find the right balance is that many factors affect the way these medications are utilized in the body. Everyone needs an individualized dose — the foods you eat and other drugs can change the effectiveness of the blood-thinning medication, said Dr. Marc Siegel, an internist at the NYU Langone Medical Center in New York City.

To avoid these complications, people on these medications have to have their blood frequently monitored, especially when first starting therapy. Until recently, this meant a visit to the doctor’s office.

But now, several devices are available for home testing. The cost of the devices averages around $2,000, according to Dolor, and the supplies for each test cost about $5 to $10. In 2002, Medicare approved coverage for home testing for patients on anticoagulation therapy with prosthetic heart valves, and in 2008, it expanded the availability of home testing to those who need long-term anticoagulation therapy, such as people with the heart condition atrial fibrillation.

In the current study, the researchers randomly assigned 2,922 people who were taking warfarin because they had a mechanical heart valve or had atrial fibrillation to either test weekly at home or monthly in a clinic.

The patients used finger-stick devices approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for home use. They were trained to use the devices, which measure how fast the blood clots, and the results were phoned in to a physician’s office to discuss changing the medication dose as needed.

The study volunteers were then followed for between two and 4.75 years, according to the study.

A total of 164,626 home tests were performed, and about 87 percent of the study volunteers adhered to their home testing routine.

Over the study period, 271 people in the home-testing group had a stroke, a major bleeding event or died, compared to 285 in the clinic-tested group. The self-testing group reported significantly more minor bleeding episodes, but it had a small, but statistically significant improvement in the time patients spent in the target range for the medication.

The home-test group also reported slightly higher patient satisfaction scores, according to the study.

Dolor said the researchers didn’t design the study to figure out why the home-test group might be more satisfied, but suggested that the convenience of home testing and not having to go out to the doctor’s office likely play a role. She said that patients may also feel more in control, and may feel that they have a better understanding of their condition.

“More frequent monitoring is much safer and ideal. If the technical accuracy of home monitoring is the same, and we can be assured that the patient is using home monitoring properly, then I don’t have a problem with it,” said Siegel.

Although the current study didn’t find a significant difference in preventing serious outcomes, Dr. L. Bernardo Menajovsky, director of the anticoagulation clinic at the Scott and White Healthcare Center for Diagnostic Medicine in Temple, Texas, noted that a significant number of healthier people were enrolled in it.

“About 40 percent of the study population were at low risk to have bad outcomes,” he said, adding that if the researchers had been able to look at more people in a high-risk group, they may have seen an improvement with the more frequent home monitoring.

But, “home testing alone isn’t going to be the answer [for improving complications]. We need good patient education, and after that, the next step is home management,” he said, explaining that people could be trained to test themselves and then make adjustments to their medication doses, similar to the way diabetes is managed.

The study was sponsored by the VA’s Cooperative Studies Program.

More information

To learn more about blood thinners, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.