FRIDAY, Sept. 21 (HealthDay News) — In what might one day prove to be a breakthrough for those suffering from sickle cell anemia, new research suggests that bone marrow transplants based on partially matched donors can, in some cases, turn out as well for patients as fully matched transplants.

But, the finding is based on a very small study involving just 17 patients, and was described as “preliminary” in nature.

Still, with fully matched donors in drastically short supply, the notion that so-called “half-matched” transplants might also work raises the possibility that many more patients could avail themselves of a treatment for what can be an extremely painful, debilitating and ultimately fatal illness.

“We’re trying to reformat the blood system and give patients new blood cells to replace the diseased ones, much like you would replace a computer’s circuitry with an entirely new hard drive,” study author Dr. Robert Brodsky, director of the division of hematology at Johns Hopkins and the Johns Hopkins Family Professor of Medicine and Oncology in Baltimore, said in a university news release.

“[But] while bone marrow transplants have long been known to cure sickle cell disease, only a small percentage of patients have fully matched eligible donors,” he added.

Brodsky and his colleagues discussed the donor dilemma and their efforts to broaden transplant options in the Sept. 6 online edition of the journal Blood.

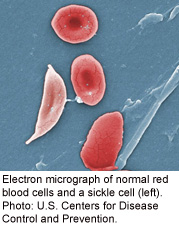

Roughly 100,000 Americans live with sickle cell anemia, a genetic disorder that impedes the normal workings of hemoglobin molecules responsible for transporting oxygen within red blood cells. The stiffening and misshaping of such cells into the telltale form of a “sickle” ultimately leads to cell clumping. In the end, oxygen delivery to organs and tissues shuts down.

As the illness progresses, patients typically struggle with excruciating pain, along with a risk complications, including kidney failure, stroke, lung disease and blood clots. Many die of the disease before the age of 50.

Treatment is often centered around the use of narcotics for pain control, along with frequent blood transfusions and hospitalizations.

The good news: bone marrow transplants involving fully matched tissue donors have shown the potential to effect a cure in some patients.

The bad news: the vast majority of patients are black (with about one in every 400 blacks struck by the disease) and national donor registries are limited, leaving many to wait in vain for a donor match.

Brodsky and his team performed bone marrow transplants involving both fully matched donors (three cases) and half-matched donors (14 cases), among patients between 15 and 46 years of age.

Both full and partial donor matches were drawn from family members such as parents, children and/or siblings. And all patients underwent a comparatively “gentle” pre-procedure prep regimen of immuno-suppression, chemotherapy and radiation treatment, the study authors said.

The result: 11 of the 17 transplants were deemed “successful.” And of these 11 patients, eight had undergone half-matched operations.

The study authors said there were no fatalities. They concluded that the half-matched approach appeared to produce a success rate greater than 50 percent.

Dr. Zora Rogers, clinical director of the General Hematology Program at the Children’s Medical Center in Dallas, said that while the findings are “encouraging,” they should be interpreted with caution.

“First of all,” she said, “it’s important to recognize that this half-matched procedure performed predominantly among adults was not as good as a fully matched transplant performed among children would be, where the cure rate exceeds 90 percent. In fact, when you look at the 11 patients they say got better, six of them, if you will, were really ‘cured’ of their disease, while the other five of them remained a mixture of someone with the disease and without.”

“But more importantly,” Rogers added, “I would also point out that what a success rate of a little bit over 50 percent means is that you could go through this very big deal transplant, put your life at risk, and have it fail about half the time. Now, sickle cell is a horrible disease. Don’t get me wrong. But unlike in leukemia or other malignancies where a transplant is your only hope, with sickle cell it’s just an option. So, for patients who wish to pursue a cure this may expand their choices. But they need to consider this information carefully.”

More information

For more on sickle cell anemia, visit the U.S. National Library of Medicine.