THURSDAY, Oct. 20, 2016 (HealthDay News) — Researchers say that based on laboratory studies, the cells of black Americans mount a much stronger immune response to infection than those of European-Americans.

That hearty response might have a downside, though. It could play a role in black Americans’ higher risk for heart disease, stroke and autoimmune inflammatory diseases, the researchers said.

The findings might lead to treatments that reduce chronic health risks for African-Americans, according to the researchers.

The strength of the immune response was directly related to the percentage of genes derived from African ancestors, said senior researcher Luis Barreiro. He’s an assistant professor at the University of Montreal’s Department of Pediatrics and researcher at the Sainte-Justine University Hospital Center in Montreal.

“Basically, the more African you have in your genome, the stronger you’re going to respond to infection,” Barreiro said.

But a strong immune response uses inflammation to attack and defeat infection, he said.

Too much inflammation can cause chronic high blood pressure, damage organs such as the heart, and increase susceptibility for autoimmune diseases such as lupus and Crohn’s disease, Barreiro said.

“The immune system of African-Americans responds differently, but we cannot conclude that it is better, since a stronger immune response also has negative effects,” he said.

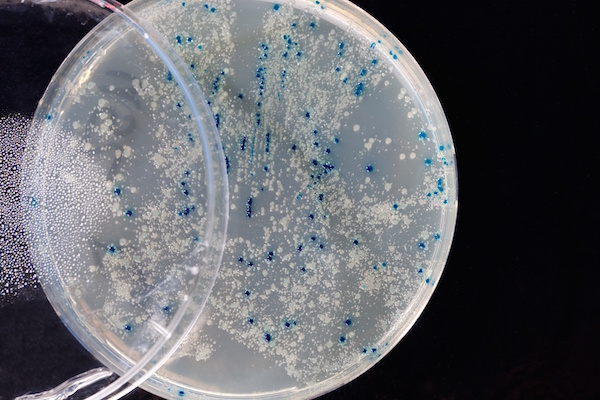

Barreiro and his colleagues from several U.S. universities conducted their study using white blood cells drawn from 175 Americans, 80 of whom were of African descent. In the lab, the researchers infected the white blood cells with listeria and salmonella bacteria, so they could observe the immune response.

After 24 hours of infection, white blood cells from African-Americans killed the bacteria three times faster, the researchers reported.

Genetic differences between blacks and whites due to evolution and natural selection appear to be behind this difference in immune response, Barreiro said. Researchers identified thousands of genes that showed race-based differences in a person’s genetic response to infection.

“For the first time, we were able to characterize what genes and regulatory pathways are different between the two populations,” he said. “For many of these differences, we could actually map their genetic basis.”

In fact, one of the study’s strengths was that it didn’t categorize people as being either European or African when it came down to their genetics, said Dr. David Rosenthal.

“They [the researchers] calculated the amount of genetic material that was African versus European — not thinking of people as either being X or Y, but thinking about people being on a gradient between one ancestry and another,” said Rosenthal, who was not involved with the study.

Rosenthal is medical director of the Center for Young Adult, Adolescent and Pediatric HIV and an attending allergy/immunology physician with Northwell Health in Great Neck, N.Y.

A second study by French researchers came to the same conclusion, using white blood cells drawn from 200 people of either European or African ancestry.

Teams from both studies said the genetic divergence could be explained by the Neanderthals, who colonized Europe but not Africa before they became extinct about 40,000 years ago. Barreiro’s team found that about 3 percent of the genes involved in the differences in immune responses between African-Americans and European-Americans came from Neanderthals.

Other evolutionary processes also might be at play, Barreiro said.

It could be that when early humans migrated north out of Africa, they encountered less infection from weaker bacteria and viruses. “You just by chance wind up reducing your response,” he said. “You don’t need to favor these very strong inflammatory responses.”

Another explanation could be that people who remained in Africa were continually infected with parasites that impede or stop inflammatory responses, Barreiro said.

“If you are almost permanently infected with parasites, you need an even stronger inflammatory response to overcome the influence of the parasites,” he said. “When you leave Africa and come to an environment like the U.S., where that pressure disappears, your inflammatory response now is too exacerbated.”

This new genetic information could guide the way to treatments that reduce chronic health risks for African-Americans, Barreiro concluded.

“The genes and pathways we’ve identified constitute good candidates to explain differences we are seeing in disease between the two population groups,” he said. “Now that we have these genetic variants, we can test if these variants are associated with differences in susceptibility to diseases.”

Rosenthal agreed. “These sorts of studies basically give you a fishing expedition, to find targets or possible genes that could be important,” he said. “Future studies need to zero in on those genes and determine if they are important or not.”

Both studies appeared Oct. 20 in the journal Cell.

More information

For more on racial differences in chronic health risks, visit the Center for American Progress.

Copyright © 2026 HealthDay. All rights reserved.