WEDNESDAY, Dec. 21 (HealthDay News) — New research suggests that the outer edges of the brain are thinner in older people who may be destined to develop Alzheimer’s disease, but there’s currently no way to use the information to help people fend off dementia.

Still, the findings could help researchers test Alzheimer’s medications by allowing them to track the progression of the disease, said study co-author Dr. Brad Dickerson, an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School.

Alzheimer’s disease is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, and the number of deaths has risen in recent years. There’s no cure for the disease.

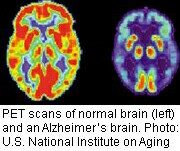

In the new study, researchers focused on the thickness of the edges of the brain, known as the cortex. “We’re looking at the parts of the cortex that are particularly vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease, parts that are important for memory, problem-solving skills and higher-language functions,” Dickerson said.

Previous research found that several areas of the cortex were smaller in people with dementia from Alzheimer’s. “It’s like an orange that’s shriveling. The thickness of the outer skin might get thinner as it dries out,” Dickerson said.

In the new study, researchers examined the MRI brain scans of 159 people with an average age of 76; about half were men. Three years later, the participants took tests designed to measure how their brains were functioning.

The findings appear in the Dec. 21 online issue of the journal Neurology.

The 15 percent of participants with the thinnest brain areas performed the worst on the tests: About one in five of them experienced cognitive decline. They also showed increases in signs of abnormal spinal fluid, a possible sign of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

“That suggests they may be developing symptoms,” Dickerson said.

A lower number — 7 percent — of the participants in the middle range of brain thinness experienced cognitive decline. None of the people with the least thin brain areas developed problems.

So are the scans appropriate as tools to figure out whether patients are on the road to Alzheimer’s?

Cost doesn’t appear to be a major challenge at this point. It’s not clear how much the MRI scans might cost at doctor’s offices, Dickerson said. However, they’re only a few hundred dollars each in the research world.

Also, many older people already receive MRI scans of the brain for other reasons, said Dr. Raj Shah, medical director of the Rush Memory Clinic, in Chicago.

But with no cure for Alzheimer’s, the best use for the scans will be to help researchers figure out if medications work, Dickerson said.

Cathy Roe, an assistant professor of neurology at the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Washington University School of Medicine, in St. Louis, said the findings could have value down the line. “Right now, there is not much we can do to delay the progression of dementia,” said Roe, who’s familiar with the findings. “But once effective treatments are identified, this research could help to identify which patients should receive that treatment and when they should receive it.”

More information

For more about Alzheimer’s disease, try the U.S. National Library of Medicine.