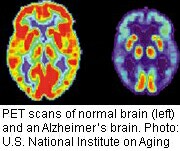

MONDAY, Jan. 28 (HealthDay News) — While there’s still no definitive means of diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease in living patients, PET scan technology may help suggest the onset of the disease. Now, experts are issuing new guidance on which patients might stand to benefit most from the expensive scans.

Amyloid brain plaque is considered one hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. With PET (positron emission tomography) imaging, amyloid can be identified while patients are still alive.

According to the guidelines, people who should be considered for a scan include the following:

- People with persistent or progressive unexplained memory problems or confusion and those with problems on standard tests of thought and memory.

- People with possible Alzheimer’s, but whose symptoms don’t present in the usual way.

- People with progressive dementia before age 65.

On the other hand, PET amyloid scanning is not appropriate for people over 65 who are already known to have Alzheimer’s, the guidelines say. Moreover, people who do not have any symptoms or with little medical evidence to support a diagnosis will not benefit from the scan.

The finding of brain amyloid in itself does not constitute a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia, the guidelines emphasize. It’s just one tool to be used along with information from the patient’s history and clinical examination.

“Amyloid imaging is not for every patient with Alzheimer’s disease or with memory problems or even the ‘worried well,'” said Maria Carrillo, vice president for medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association and guideline co-author.

Developed jointly by the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the guidelines were published online Jan. 28 in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. The task force reviewed scientific literature and considered clinical scenarios.

These guidelines are particularly timely, Carrillo said, because most patients with dementia are 65 and older, and an advisory committee of the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid will be considering this topic on Jan. 30 to decide whether or not the cost of these scans will be covered under the programs.

PET scans can cost anywhere from $3,000 to $6,000 or more, she said.

“Amyloid imaging is appropriate for select use and is really limited to increase certainty of a diagnosis when there are uncertain conditions,” Carrillo said. In these cases, imaging helps because it can aid the doctor in deciding what treatment should be given, she said.

For patients with persistent or progressing memory or thinking problems, the test can increase the certainty that they are dealing with an Alzheimer’s type of dementia.

If there is no plaque in the brain, the doctor should then look for other causes of the problem such as small strokes or another type of dementia, she said.

Although little effective treatment for Alzheimer’s exists, it’s important for patients to know what they are dealing with, Carrillo said. “For us as a patient advocacy group, that’s critical,” she said. Many people are relieved to know even if it’s a bad diagnosis, she said.

“What comes with that is not only the relief, but the beginning of not only a medical plan, but planning for the future,” Carrillo said. “Even talking about the possibility of joining a clinical trial,” she said.

Until recently, amyloid brain scans have mostly been used in research to determine which patients can be part of clinical trials and whether or not treatments are having results.

“These are the first guidelines for clinical use of amyloid imaging,” said Dr. Sam Gandy, associate director of the Mount Sinai Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, in New York City.

This has been coming since 2002, but now the promise has been realized and anyone who should have amyloid imaging and can get to a nuclear medicine unit will be able to have the scan, he said.

“Another milestone is that never again will a doctor have to say, ‘we can’t tell for sure until your loved one dies and we look at the brain during an autopsy,'” Gandy said.

“On the downside, while scanning of healthy ‘worried well’ people is explicitly discouraged and disapproved, that is already happening and I am not sure that these guidelines will attenuate that demand,” he said. “Persistent people will always find someone to write the script. So, this challenge remains.”

More information

To learn more about Alzheimer’s disease, visit the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.