TUESDAY, April 17 (HealthDay News) — New research adds to the growing pile of scientific strategies aimed at revealing beta-amyloid (protein) plaques, the brain-clogging fragments that have been associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

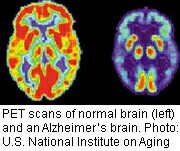

In a study funded by Bayer Healthcare Berlin, researchers report that they were able to use a drug and PET scans to successfully detect plaques in the brains of patients whose Alzheimer’s was confirmed after death.

More than 200 patients near death — including some with apparent Alzheimer’s disease — underwent the PET scans. They received doses of the drug florbetaben, which was used as a “tracer” to allow the PET scans to detect the plaques.

Thirty-one patients died and had autopsies to confirm that they had Alzheimer’s disease. The researchers determined that one way of interpreting the PET scan results correctly pinpointed Alzheimer’s disease 100 percent of the time and correctly ruled it out 92 percent of the time.

“These results confirm that florbetaben is able to detect beta-amyloid plaques in the brain during life with great accuracy and is a suitable biomarker,” study author Dr. Marwan Sabbagh, director of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Ariz., said in an American Academy of Neurology news release.

“This is an easy, noninvasive way to assist an Alzheimer’s diagnosis at an early stage. Also exciting is the possibility of using florbetaben as a tool in future therapeutic clinical research studies where therapy goals focus on reducing levels of beta-amyloid in the brain,” Sabbagh added.

Dr. William Jagust, a professor of neuroscience at the University of California, Berkeley’s Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, said several companies are developing ways to detect beta-amyloid plaques. “It’s a very important development in our field,” he said. “The big practical question is how much is this going to cost — it may cost $2,000 or more to get a scan — and whether it is worth it considering what we can do for such patients.”

There’s no cure for Alzheimer’s and no way to reverse it, although drugs are available to treat symptoms. Still, Jagust said, detecting beta-amyloids may be helpful as a way to determine whether experimental drugs actually work.

The study is slated for presentation at the American Academy of Neurology’s annual meeting, which starts April 21 in New Orleans.

The data and conclusions should be viewed as preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

More information

For more about Alzheimer’s disease, try the U.S. National Library of Medicine.