THURSDAY, Oct. 21 (HealthDay News) — Researchers report that, in mice at least, tissue from outside the brain that contains misfolded beta-amyloid protein can travel and “infect” the brain.

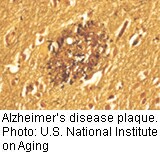

Beta-amyloid protein plaques, which clutter the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, have been strongly implicated in the genesis of this neurodegenerative disease.

The experiment involved injecting amyloid-containing brain tissue from older mice into the abdomens of younger mice. Several months after the injections, the younger mice showed evidence of amyloid in their brains.

The authors of the study, publishing in the Oct. 22 issue of Science, suggest that amyloid protein may have prion-like qualities. Prions are made primarily of protein and can be transmitted to trigger brain ailments such as lethal Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (“mad cow disease”).

However, outside experts emphasized that the results of the experiment should not lead people to think that Alzheimer’s is a transmissible disease.

“It would be really unfortunate if this caused a lot of people to start worrying about Alzheimer’s disease as an ‘infectious’ disease,” said William Thies, chief of medical and scientific affairs at the Alzheimer’s Association. “There’s absolutely no evidence of that . . . Even prion disease only comes from ingesting brain material, so I think this is very basic research in its earliest stages and drawing any conclusions to clinical aspects of Alzheimer’s disease would be foolish.”

Dr. Anton Porsteinsson, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Care, Research and Education Program at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York, agreed that the findings are “scientifically intriguing” but still far from “real life.”

“We have no evidence that someone with Alzheimer’s disease is shedding or transmitting a lot of beta-amyloid, [and] that it could even be remotely then transmitted into other people. It sounds more like beta-amyloid is bad, and that it initiates a vicious cycle,” he added. “We have no idea how would you ever ingest flawed beta-amyloid. Where does it come from? How does it get into your body?”

Still, he added, the findings may offer “up new venues in terms of interventions, whether it’s the type of intervention or the timing of interventions. . . We’re certainly looking for new ways right now to push the field forward. I think this is going to be interesting to watch, and there are a growing number of reports about interactions between misfolding proteins or proteins behaving badly.”

And the study is novel in the fact that “the researchers injected the amyloid-containing brain tissue into the cavity where the abdominal organs are and it got into the brain,” said Ian Murray, an assistant professor of neuroscience and experimental therapeutics at Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine in College Station.

The new study was led by Mathias Jucker, of the University of Tubingen in Germany, in collaboration with scientists in Switzerland and at Emory University in Atlanta. The team gave two injections of brain tissue containing amyloid from aging mice into the abdominal areas of 2-month-old female mice.

Seven months later, the younger female mice had evidence of amyloid in their brains.

But there were also important limitations to the study.

For one thing, the authors did not delineate what was in the brain tissue injected into the younger mice.

“It’s brain material. It has all sorts of other things in it,” Thies said. “What you’re seeing in the second animal is not clear at all and is as likely to be some sort of chemical change as it is any kind of infectious process.”

And the particular mice models used in the study are engineered to produce beta-amyloid anyway, Porsteinsson pointed out.

More information

The Alzheimer’s Association has more on this disease.